Robert Liston was a renowned 19th century Scottish surgeon, known for his groundbreaking techniques and remarkable surgical skills – and speed. Nicknamed ‘the fastest knife in the West End’, he could famously amputate a leg in under 30 seconds, at a time when there was no anaesthetic and when only around half of patients would survive an operation.

Liston was committed to improving surgical practices with his innovative approaches – he was the first surgeon in Europe to operate with patients under ether anaesthesia, and was known for his emphasis on patient welfare and education that set him apart from his peers. His contributions continue to influence modern surgical techniques today.

Here we explore the life of Robert Liston, and his legacy on the medical profession.

Early life

Robert Liston was born on 28 October 1794, in West Lothian, Scotland. His mother died when he was 6, so he was raised and taught by his father. Liston’s interest in medicine emerged at an early age, and he entered the Edinburgh University’s Medical School in 1808 aged 14, studying under some of the most prominent medical practitioners of the time. He showed exceptional talent and dedication to his studies.

In 1810 Liston began his medical training as assistant to famed anatomist, Dr John Barclay. In 1814, he was appointed house surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, and was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons in London two years later aged 22.

Liston had already gained a reputation for being argumentative, straight-talking and intimidating, and after a disagreement with Barclay, opened his own anatomy class in 1818. Liston became known as a fearless surgeon, willing to operate on patients other surgeons deemed untreatable. His criticism of surgeons he did not respect and charges that he was enticing patients towards his own practice briefly led to Liston being dismissed by the Infirmary, but he was later reinstated.

Nevertheless, Liston was later appointed Professor of Surgery as the University College Hospital in London aged 34, and remained working there for the rest of his life.

19th century operations

In the early 19th century, before the development of anaesthesia, amputations were performed on fully conscious patients who were able to feel the excruciating pain of the surgery. Speed was crucial, and thus surgeons who removed limbs the quickest gained popularity. A skilled surgeon could amputate a leg in under three minutes.

During the procedure, a screaming patient was restrained on a wooden bench by ‘dressers’, who would also assist the surgeon with ligatures, knives and dressings. Although unknown at the time, rapid operations minimised the exposure of tissue to microbes and infection, however many patients still died from shock, blood-loss, and post-operative infection.

In the early 19th century, most surgeons including Liston believed surgery was often a patient’s last resort. When a bone had penetrated the skin, amputation was often the only option, the alternative was gangrene, blood poisoning and death.

Watch Now

Watch Now‘Time me, gentlemen, time me!’

Before developments such as blood transfusions, patient survival also depended largely on how quickly the surgeon could manage bleeding.

Liston quickly gained recognition for his surgical skills, precision, speed and efficiency in his operations at University College Hospital in London in the early 1840s. The chances of dying from a Liston amputation were around 1 in 6, significantly better than the average Victorian surgeon.

Liston emphasised the importance of minimising patient pain and reducing the duration of surgical procedures, introducing various techniques to streamline operations, including the use of rubber tubing ligatures to control bleeding, instead of traditional silk ligatures.

Medical students and visiting surgeons would pack Liston’s surgical theatre, eager to witness his techniques. Liston would often nod to his audience saying “Time me gentlemen, time me!”. His above-the-knee amputations from incision to final suture were completed in less than 30 seconds, earning him the nickname, ‘The Fastest Knife in the West End’.

The perils of speed

Whilst Liston was celebrated for his speed, it sometimes led to unfortunate accidents. On one occasion, Liston accidentally removed a patient’s testicles along with the leg being amputated due to the swiftness of his work.

Additionally, Liston holds the distinction of being the only surgeon said to have performed an operation with a 300% mortality rate. During a high-speed amputation, he inadvertently severed his assistant’s fingers and slashed a spectator’s coat, causing the shocked spectator to faint. All three later died – the patient and assistant from sepsis, and the spectator from shock.

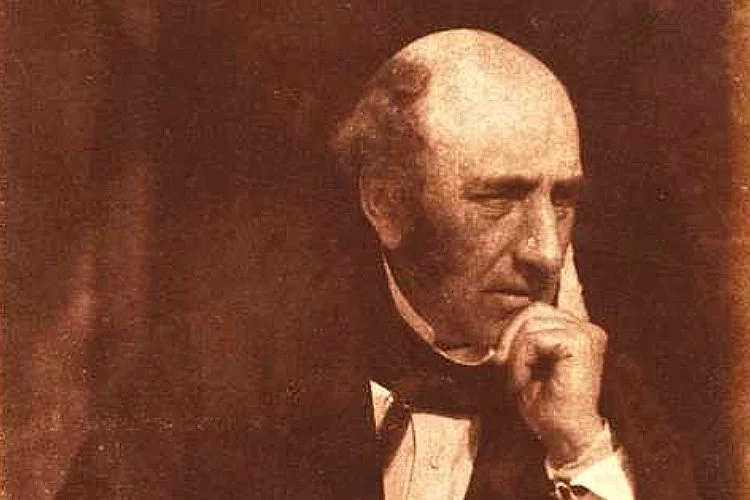

Scottish surgeon Robert Liston. (Left: photograph circa 1845 by Hill & Adamson)

Surgical innovations

Although known to clench a knife in his teeth while his hands were occupied, Liston had a strong sense of cleanliness and order in his surgical procedures. He was one of the few surgeons known to wash his hands before operations, long before the formulation of germ theory and antiseptics. He also always wore a clean apron for each operation – uncommon for the time, as most surgeons wore the same filthy apron as evidence of their abilities and experience.

Liston also shaved surgical sites prior to incision and insisted on clean surgical sponges, and cold water-soaked dressings only.

While many believed the pain of surgery acted like a stimulant and was beneficial for healing, Liston was an early advocate of anaesthesia. He performed Europe’s first operation using anaesthesia on 21 December 1846. His patient, Frederick Churchill, caused amusement in the operating theatre when he woke after the amputation asking Liston when he was going to begin. Nevertheless, the combination of Victorian gas lighting and the anaesthetic gas was potentially lethal.

Liston also made significant contributions to surgical techniques, revolutionising amputations by using a long straight knife with sharpened edges, known as the ‘Liston knife’, which became a standard amputation tool. He also invented forceps with a built-in snap to control arterial bleeding.

Liston recognised patient fears regarding surgery, and believed in the importance of informing and reassuring them, paying great attention to post-operative care too. He also challenged notions that experience and ability were solely based on age, arguing that volume of cases determined experience, and that surgeons should take courageous actions.

Set of four Liston-type amputation knives

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Wellcome Images / Photo number: L0057237 / CC BY 4.0

Personality

Liston was tough and demanding. Standing at 6 foot 2 inches tall, his height contributed to the speed and physicality of his surgical operations – and his imposing presence. While he could be harsh towards trainees who didn’t meet his standards during operations, he was rumoured to be kind outside of work. Liston strongly advocated for the humane treatment of patients, emphasising the importance of treating them with dignity, obtaining their consent, and displaying empathy.

Liston also firmly opposed practices that he deemed unethical, objectionable and unscientific, and confronted surgeon Robert Knox, believed to have been involved in the infamous William Burke and William Hare serial murders and grave robberies from 1827-1828 that supplied bodies for dissection by anatomy students.

Death and legacy

Robert Liston died in 1847 aged 53 of a ruptured aortic aneurysm. His funeral was attended by over 500 students, friends and pupils, and he was buried at Highgate Cemetery.

Whilst a highly respected surgeon, Liston was not immune to criticism. Some questioned his focus on speed, suggesting it compromised patient safety and thoroughness, and his brash and confrontational personality sometimes led to strained relationships with colleagues.

However, Robert Liston’s contributions to the medical profession were significant. His use of flaps in amputations had a substantive impact on surgical technique, as did his innovations in commonplace instruments such as his amputation knife, locking vascular forceps, and long splint. He also incorporated hygienic practices that foreshadowed the concept of antiseptic, sterile operating environments.

Liston understood patient fears about surgery and was a dedicated educator who imparted his knowledge and techniques to his students, holding them to high standards while fostering an environment for continual improvement which continues to influence modern surgical techniques today.