One of the great events which took place in the narrative history of Roman Britain was the campaigns of the warrior Emperor Septimius Severus, who tried to conquer Scotland in the early 3rd-century.

Severus became the emperor in AD 193 in the Year of the Five Emperors. His attention was drawn to Britain quite quickly because he had to face a usurpation attempt in AD 196-197 by the British Governor, Clodius Albinus.

He only narrowly defeated Albinus at the titanic Battle of Lugdunum (Lyon), in what may have been one of the biggest engagements in Roman history. From that point, Britain was on his map.

Severus’ attention turns to Britain

Now, Severus was a great warrior emperor. In the AD 200s he was coming towards the end of his life, and was looking for something to give him one last taste of glory.

Bust of Septimius Severus. Credit: Anagoria / Commons.

He’s already conquered the Parthians, so he wants to conquer the Britains because those two things together will make him the ultimate emperor. No other emperor has conquered the far north of Britain and the Parthians.

So Severus sets his target on the far north of Britain. The opportunity comes in AD 207, when the British governor sends him a letter saying that the whole province is in danger of being overrun.

Let’s reflect on the letter. The governor is not saying that the north of Britain is going to be overrun, he’s saying that the whole province is in danger of being overrun. This conflagration he’s talking about is in the far north of Britain.

Watch Now

Watch NowThe arrival of Severus

Severus decides to come over in what I call the Severan Surge; think of the Gulf Wars. He brings over an army, a campaigning force of 50,000 men, which is the largest campaigning force which has ever fought on British soil. Forget the English Civil War. Forget the Wars Of The Roses. This is the largest campaigning force ever to fight on British soil.

In AD 209 and AD 210, Severus launches two enormous campaigns into Scotland from York, which he’s established as the imperial capital.

Imagine this: from the time of Severus coming over in 208 to his death in 211, York became the capital of the Roman Empire.

He brings his imperial family, his wife, Julia Domina, his sons, Caracalla and Geta. Severus brings the imperial fiscus (the treasury), and he brings senators over. He establishes family members and friends as the governors in all the key provinces around the empire where there may be trouble, in order to secure his rear.

Listen Now

Listen NowA genocide in Scotland?

Severus launches campaigns north along Dere Street, eviscerating everything in his way in the Scottish Borders. He fights a terrible guerrilla war against the native Caledonians. Ultimately, Severus defeats them in 209; they rebel over the winter after he’s gone back to York with his army, and he defeats them again in 210.

In 210, he announces to his troops that he wants them to commit a genocide. The soldiers are ordered to kill everybody they come across in their campaigning. It would appear that in the archaeological record now there is evidence to suggest this actually did occur.

A genocide occurred in the south of Scotland: in the Scottish borders, Fife, the Upper Midland Valley below the Highland Boundary Fault.

It looks like the genocide may have occurred because re-population took about 80 years to really take place, before the far north of Britain becomes problematic for the Romans again.

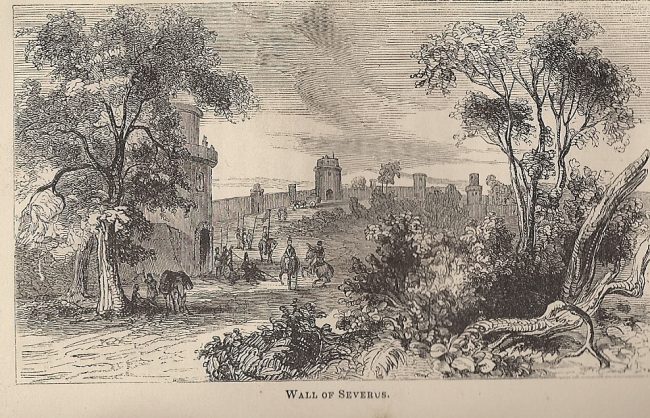

An engraving by an unknown artist of the Antonine / Severan Wall.

The legacy of Severus

It doesn’t help Severus though, because he died in the freezing cold of a Yorkshire winter in February AD 211. For the Romans to try and conquer the Far North of Scotland, it was always about political imperative.

With Severus’ death, without that political imperative to conquer the far north of Scotland, his sons Caracalla and Geta flee back to Rome as fast as they can, because they’re squabbling.

By the end of the year, Caracalla had Geta killed or killed Geta himself. The far north of Britain is evacuated again and the whole frontier dropped back down to the line of Hadrian’s wall.

Watch Now

Watch NowFeatured image credit: Dynastic aureus of Septimius Severus, minted in 202. The reverse feature the portraits of Geta (right), Julia Domna (centre), and Caracalla (left). Classical Numismatic Group / Commons.