By far the most successful woman to rule ancient Egypt as pharaoh, Hatshepsut (c.1507-1458 BC) was only the third woman to reign as female ‘king’ of Egypt in 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history. Moreover, she achieved unprecedented power, adopting the full titles and regalia of a pharaoh and so becoming the first woman to reach full influential potential within the position. By comparison, Cleopatra, who also achieved such power, ruled 14 centuries later.

Though she was a dynamic innovator known for developing trade routes and constructing elaborate structures, Hatshepsut’s legacy was almost lost forever, since her stepson Thutmose III destroyed nearly all trace of her existence after her death.

Details of Hatshepsut’s life only began to emerge in the 19th century, and initially confused scholars, since she was often depicted as a man. So who was the remarkable ‘king’ of Egypt Hatshepsut?

1. She was the daughter of a pharaoh

Hatshepsut was the elder of two surviving daughters born to pharaoh Thutmose I (c.1506-1493 BC) and his queen, Ahmes. She was born in around 1504 BC during a time of Egyptian imperial might and prosperity, known as the New Kingdom. Her father was a charismatic and military-driven leader.

Scene of a statue of Thutmose I, he is depicted in the symbolic black color of deification, the black color also symbolizes rebirth and regeneration

2. She became queen of Egypt aged 12

Normally, the royal line passed from father to son, preferably the son of the queen. However, since there were no surviving sons from Thutmose I and Ahmes’ marriage, the line would be passed to one of the pharaoh’s ‘secondary’ wives. Thus, the son of a secondary wife Mutnofret was crowned Thutmose II. After her father’s death, 12-year-old Hatshepsut married her half-brother Thutmose II and became queen of Egypt.

3. She and her husband had one daughter

Though Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter, they failed to have a son. Since Thutmose II died young, possibly in his 20s, the line would yet again have to pass to a child, who became known as Thutmose III, via one of Thutmose II’s ‘secondary’ wives.

Listen Now

Listen Now4. She became regent

At the time of his father’s death, Thutmose III was likely an infant, and was deemed too young to rule. It was a New Kingdom practice for widowed queens to act as regents until their sons came of age. For the first few years of her stepson’s reign, Hatshepsut was a conventional regent. However, by the end of his seventh year, she had been crowned king and adopted a full royal titulary, effectively meaning that she co-ruled Egypt along with her stepson.

Statue of Hatshepsut

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

5. She was depicted as a man

Early on, Hatshepsut was depicted as a queen, with a female body and garments. However, her formal portraits then began to show her as a man, wearing the regalia of kilt, crown and false beard. Rather than it demonstrating that Hatshepsut was trying to pass off as a man, it was instead to show things as they ‘should’ be; in showing herself as a traditional king, Hatshepsut made sure that is what she became.

Moreover, political crises such as a competing branch of the royal family meant that Hatshepsut may have had to declare herself as king to protect her stepson’s kingship.

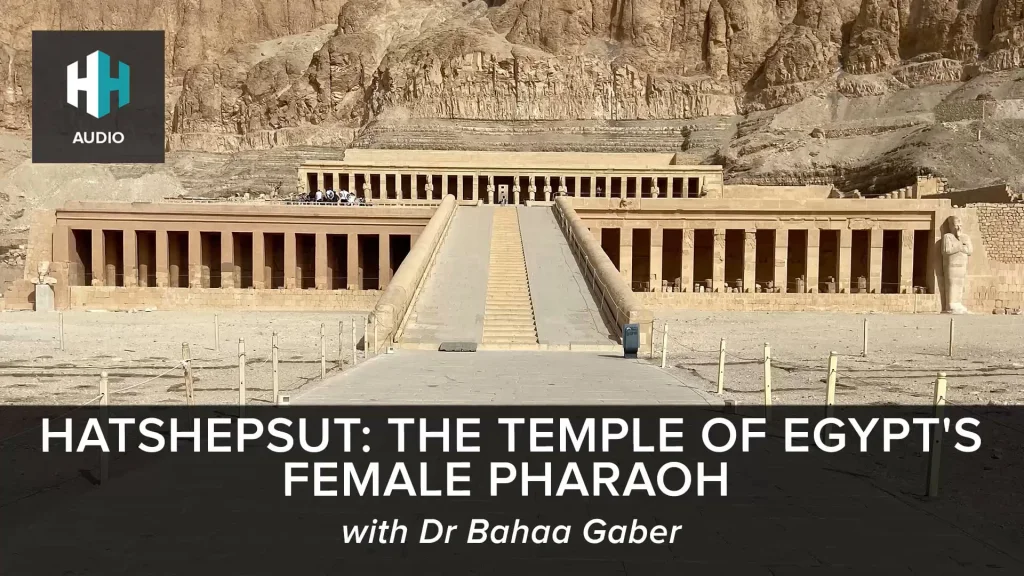

6. She undertook extensive building projects

Hatshepsut was one of ancient Egypt’s most prolific builders, commissioning hundreds of construction projects such as temples and shrines across both Upper and Lower Egypt. Her most supreme work was the Dayr al-Baḥrī temple, which was designed to be memorial site for her and contained a series of chapels.

Listen Now

Listen Now7. She strengthened trade routes

Hatshepsut also expanded trade routes, such as the seaborne expedition to Punt on the East African coast (possibly modern-day Eritrea). The expedition brought gold, ebony, animal skins, baboons, myrrh and myrrh trees back to Egypt. Remains of the myrrh trees can be seen at the Dayr al-Baḥrī site.

8. She extended her father’s tomb so she could lie next to him in death

Hatshepsut died in her twenty-second regnal year, possibly around the age of 50. Though no official cause of death survives, studies on what is thought to be her body indicate that she might have died of bone cancer. In an effort to legitimise her reign, she had her father’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings extended and was interred there.

Aerial view of Queen Hatshepsut mortuary temple

Image Credit: Eric Valenne geostory / Shutterstock.com

9. Her stepson erased many traces of her

After his stepmother’s death, Thutmose III ruled for 30 years and proved himself to be a similarly ambitious builder, and a great warrior. However, he destroyed or defaced almost all record of his stepmother, including the images of her as king on temples and monuments. It’s thought that this was to erase her example as a powerful female ruler, or close the gap in the dynasty’s line of male succession to only read Thutmose I, II and III.

It was only in 1822, when scholars were able to read the hieroglyphics on the walls of Dayr al-Baḥrī, that Hatshepsut’s existence was rediscovered.

10. Her empty sarcophagus was discovered in 1903

In 1903, archaeologist Howard Carter discovered Hatshepsut’s sarcophagus, but like nearly all of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, it was empty. After a new search was launched in 2005, her mummy was discovered in 2007. It is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Watch on TikTok