Mary Anning was a pioneering palaeontologist and fossil collector. Her life was scarred by hardship and tragedy, but it was also punctuated by scientific firsts. Regularly risking her life to hunt for fossils, Mary made discoveries that captured the attention of the scientific elite – helping the world discover more about extinction and dinosaurs.

Although her social status and gender meant she never received the credit she deserved in her lifetime, today Mary is remembered as one of the greatest fossil hunters to have ever lived. Here are 10 facts about Mary Anning, and how what she found helped change the way we think about the world.

Watch Now

Watch Now1. She came from a poor background and had little formal education

Mary Anning was born on 21 May 1799 in Lyme Regis, Dorset – an area within what’s now called the ‘Jurassic Coast’ on the south coast of England – one of the richest locations for fossil hunting in the UK, if not in the world. Although one of 10 children, eight of her nine siblings died before reaching adulthood. Such a high childhood mortality rate sadly wasn’t unusual. Almost half the children born in the UK in the 19th century died before the age of five, with crowded living conditions contributing to infant deaths from diseases like smallpox and measles.

Mary’s father, Richard Anning, was a cabinetmaker and carpenter who supplemented his income by being an amateur fossil collector – roaming the nearby coastal cliff-side fossil beds and selling his finds to tourists. Mary’s mother was Mary Moore, known as Molly.

The Anning family were religious dissenters (Protestants separated from the Church of England) and very poor. Like many girls in Lyme Regis at the time, Mary’s education was extremely limited, but she did attend a Congregationalist Sunday school which emphasised the importance of education for the poor.

Here Mary learned to read and write, later teaching herself geology and anatomy, inspired by her pastor urging dissenters to study the new science of geology.

2. Mary had a lucky escape when nearly struck by lightning

On 19 August 1800, 15 month old Mary was being held by a neighbour, Elizabeth Haskings, who was standing with two other women under an elm tree watching an equestrian show. Lightning struck the tree, killing all three women.

Mary was rushed home by onlookers and revived in a hot bath. A doctor declared her survival miraculous, and Mary’s family said that whilst she had been a sickly baby before the event, afterwards she seemed to blossom. For years afterward members of the community attributed her curiosity, intelligence and lively personality to the incident.

The Jurassic Coast at Charmouth, Dorset, England where Mary Anning discovered large reptiles in the shales of Black Ven; Golden Cap in the near distance.

Image Credit: Wikimedia / Flickr - Kevin Walsh / CC

3. After her father’s death, Mary’s mother encouraged her to find and sell fossils

As a small child, Mary became her father’s fossil-collecting sidekick – an almost unfathomable activity for girls in Georgian times. Richard taught his daughter how to search for and clean the fossils they found on the beach, which he sold in his seafront cabinetmaker’s shop.

One night while walking over sea-cliffs in 1810, Richard slipped and fell, receiving serious injuries – he died soon after from tuberculosis. His death left the family devestated and in great debt. To help make ends meet, Mary’s brother took up work as an apprentice upholster, and Mary (now aged 11) continued her father’s fossil business, searching the coast looking for ‘curiosities’ to sell to tourists and collectors.

4. The Napoleonic wars helped Mary’s fossil business grow

During the Napoleonic Wars (taking place as Mary grew up), people were encouraged to holiday near home rather than abroad, and tourists flocked to seaside towns such as Lyme Regis. Fossil hunting was becoming a fashionable pastime for those adding to their ‘cabinets of curiosities’, and Lyme Regis was especially rich in ammonites (‘Ammon’s horn‘ at the time) as well as belemnites (‘devil’s fingers‘).

Watch Now

Watch Now5. Mary was 12 years old when she discovered the famous ichthyosaur skeleton

Around 1811 (a year after their father’s death) when Mary was 12, her brother Joseph found an unusual-looking fossilised skull in the cliffs. Mary then searched for and painstakingly dug the outline of its 5.2 metre skeleton over several months.

Local people heard about her discovery with some assuming it a monster. One of Mary’s customers, Elizabeth Philpot (who had previously given Mary a book on fossils) brought over a scientist from London, sparking scientific debate over whether the skeleton was a crocodile.

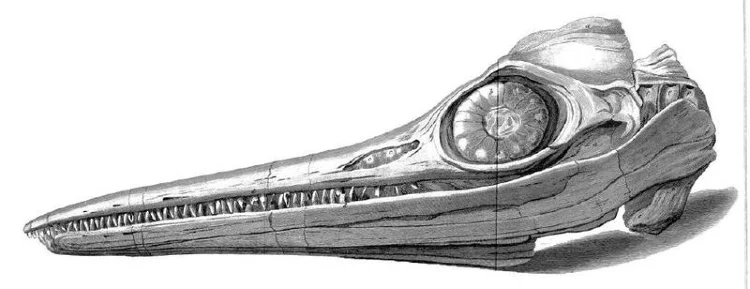

Drawing of the skull of Temnodontosaurus (originally Ichthyosaurus) platyodon found by Joseph and Mary Anning, 1814

Image Credit: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 1814 / Public Domain

At this time (48 years prior to the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species), most people assumed that unearthed, unrecognisable creatures had just migrated to far-off lands.

Mary’s groundbreaking scientific discovery was actually evidence of extinction. Georges Cuvier, the ‘father of palaeontology’, had only recently introduced the theory of extinction – considered highly controversial at the time. Many Christians were shocked, confused as to why God would let a species die out, and the mysterious creature was debated for many years.

It was eventually named Ichthyosaurus (‘fish lizard’ – we now know it was a marine reptile from 201-194 million years ago) – and was the first time scientists could study such bones. Mary was paid £23 for the skeleton, which was then sold at auction to the British Museum in 1819. Today the skeleton is at the Natural History Museum.

6. She was also the first to discover the complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus

In 1823, 12 years after her ichthyosaur discovery and now aged 22, Mary Anning became the first person to unearth a complete skeleton of another prehistoric sea creature – the plesiosaur.

Left: Autographed letter concerning the discovery of plesiosaurus, from Mary Anning. Right: Cast of “Plesiosaurus” macrocephalus fossil found by Mary Anning, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris.

Image Credit: Left: Mary Anning / Public Domain. Right: FunkMonk / CC

This marine reptile seemed so bizarre that initially scientists thought it was fake. Georges Cuvier himself disputed Mary’s find, but after a special meeting and debate was scheduled at the Geological Society of London (to which women were not accepted and thus Mary not invited), Cuvier admitted his mistake and Mary was proved correct over her plesiosaur discovery.

The specimen became the ‘holotype’ (the specimen used to describe the species), with scientists still referring to it today when studying plesiosaurs. After this second key discovery, Mary became increasingly noticed by educated geologists and scientists, who started to take her finds more seriously and sought to meet her to see her discoveries, discuss ideas and seek advice.

Pliosaur, Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni (cast), Natural History Museum, London

Image Credit: Wikimedia: John Cummings / CC

7. Sexism meant Mary wasn’t properly credited with her groundbreaking discoveries

Despite her growing reputation, the elite scientific community was hesitant to recognise Mary’s work. The male scientists who frequently bought the fossils Mary would uncover, clean, prepare and identify, often didn’t credit her discoveries in their scientific papers on the finds. Lectures were given introducing her new finds without any mention of the woman who’d discovered them. Even the Geological Society of London continued to refuse to admit Mary (not admitting women until 1904).

Not only was Mary disadvantaged in 19th century Britain through being female, the fact she was working-class and poor added to her detriment. Fossils tended to be credited to museums in the name of the rich man who had paid for them, rather than the poor, working-class woman who found them. Undeterred, Mary saved up for a shop to sell her fossils commercially, and continued searching for ancient Jurassic creatures along the coast.

8. Mary continued contributing to science, finding a Dimorphodon and pioneering the study of coporolites (fossilised poo)

In 1828 Mary uncovered a variety of bones, including a long tail and wings. News of her latest discovery travelled fast, with scientists theorising on this ‘unknown species of that most rare and curious of all reptiles’. Her find was the first remains attributed to a Dimorphodon – the first pterosaur ever discovered outside Germany. Pterosaurs had wings and were believed to be the largest-ever flying animals – later named the Pterodactyl.

Additionally, Mary pioneered the study of coprolites (fossilised dinosaur poo), able to spot these from studying rocks carefully.

Holotype of Dimorphodon (Pterodactylus) macronyx, 1830

Image Credit: Wikimedia/Flickr: Whittaker, Treacher / Public Domain

9. Her discoveries fuelled public interest in geology and palaeontology

Mary continued to unearth and sell many fossils, fuelling public interest in geology and palaeontology. People flocked to view fossil displays all around the country, and major museums struggled to match demand.

Despite her groundbreaking work, Mary still lacked respect in her local community and remained in hardship. Her childhood friend, famous geologist Henry De la Beche, was inspired to paint ‘Duria Antiquior – A More Ancient Dorset’ in 1830, and sold the prints to help raise money for Mary. The painting featured the ichthyosaur, plesiosaur and pterosaur, and was the first pictoral representation of prehistoric life based on fossil evidence.

Geologist Thomas Hawkins was also inspired by Mary’s plesiosaurus, publishing his Book of the Great Sea Dragons in 1840.

‘Duria Antiquior’ – (1830) famous watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche depicting life in ancient Dorset based on fossils found by Mary Anning.

Image Credit: National Museum Cardiff / Public Domain

10. It was only after her death that Mary began to get the respect she deserved

Mary died of breast cancer in 1847, aged just 47 and still in financial strain despite her lifetime of extraordinary scientific discoveries. (The medicine she’d been given had made her feel wobbly – misinterpreting this, locals had sneered at her, calling her a drunk).

Following her death, her friend Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society of London, broke with the society’s members-only tradition to read a eulogy at a meeting, paying homage to her achievements. She was later made an honourary member, and the society paid to have a stained-glass window in her memory installed in her local parish church. Her contributions finally began to be written about.

Mary’s outstanding contribution to palaeontology is now fully recognised. Her legacy is also marked at Lyme Regis Museum (coincidentally on the site of her birthplace and family home) and at the Natural History Museum, where several of her famous finds are on display.

The Jurassic Coast where Mary made her discoveries is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2001) – indeed the famous tongue-twister, ‘She sells seashells on the sea shore’ is often said to be based on Mary’s life, though there is no evidence for this.

In 2010, the Royal Society included Mary Anning in a list of the 10 British women who have most influenced the history of science, and a suite of rooms were named after her at the Natural History Museum. Campaigns continue for a statue of Mary, and her story loosely inspired the 2020 film, Ammonite. In 2021, the Royal Mint issued sets of commemorative 50p coins, ‘The Mary Anning Collection’, in acknowledgement of her lack of recognition as ‘one of Britain’s greatest fossil hunters’ – further helping turn the tide for Mary.