Relaunched in 2021, the trail commemorates East Sussex‘s association with the Norman conquest. The path is waymarked by 10 sculptures created by local artist Keith Pettit, each inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry.

If split into two days of 15 or so miles, the first day sees the walker set off from Pevensey, where William’s Norman army landed on 27 September 1066, and head to Battle, where the Battle of Hastings took place on 14 October 1066.

The Normans occupied the castle at Pevensey in 1066, which was once a Roman fortress and whose surviving, impressively robust curtain wall is originally Roman. The 1066 Country Walk picks up across the road where a shady corridor opens onto the Pevensey Levels. This Site of Special Scientific Interest is traversed with a steady plod over flat paths intersecting wetland meadows. The path ascends into the woody and gently rolling hills of the High Weald and soon passes directly in view of the 15th century, brick-built Herstmonceux Castle.

A few hours after setting off, I set myself down on a bench atop Tent Hill, a rise in the former medieval deer park of Ashburnham Estate. The Ashburnham family established themselves on this land a few decades after the Norman conquest, and the grounds of the grand Ashburnham Place were designed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown in 1767. More tantalising is the suggestion that the English or Norman armies may have pitched up here, with views stretching to the South Downs, on the eve of the Battle of Hastings.

A few more miles took me alongside Senlac Hill, the generally accepted site of the Battle of Hastings. Battle Abbey was built on its summit on the orders of King William to mark the battle and perhaps compensate, spiritually-speaking, for all the killing it involved. Battle offers plenty of rooms in hotels, inns and private apartments if prepared in advance. In warmer months, there are also campsites a taxi journey away.

Battle Great Wood; Farbanks Henge

Image Credit: Kyle Hoekstra

On the other hand, perhaps a more authentic means of bedding down on the route is to pitch surreptitiously beneath the conifers of Battle Great Wood, an old woodland criss-crossed by wide, muddy tracks. The early medieval English made use of the woods for charcoal and the iron industry. As the last light was split by pines, I claimed a well-drained patch between their roots onto which I unfurled a pocket-sized tent, stretched out and lit my stove.

The following morning I wriggled from my sleeping bag to a quiet dawn chorus. Overnight rain had made gummy bog of the morning’s tracks which headed south and east towards Rye. At one moment, I had to remove my bag to crawl beneath a tree that had been wrenched over a walkway. When I was far from woods and marshland, I made coffee and porridge in a field beside a big oak.

A regular sight along the 1066 Country Walk are converted oast houses, elsewhere called hop kilns. These singular, cowled buildings, where hops were dried and stored for brewing, allude to the centuries of rural hop-growing which preceded 20th century industrialisation.

The walk soon broke onto open pasture and delivered me to a sculpture known as Farbanks Henge, a circle of oak monoliths inspired by trees on the Bayeux Tapestry. Here I met Peter, a local of Battle, and walked with him on the subsequent miles of country lanes and meadows through Icklesham to Winchelsea.

As we approached Winchelsea, he pointed out the isolated ruins of a gatehouse. I was already attuned to the town’s intriguing past. Over the past day I’d listened to Alex Prestons’ 2022 novel Winchelsea, which depicts the smuggling operations which ran rife in the area in the 18th century. The town was an important node in cross-Channel trade and became affiliated with the confederation of ‘Cinque Ports’. The present town was assembled on a grid in 1288, after ‘Old’ Winchelsea was abandoned to the sea – its name plausibly deriving from language for the marshland (‘qwent’) and the beach (‘chesil’).

Rye, East Sussex, England

Image Credit: Shutterstock

I watched Peter walk eastwards for Rye, which sits on a ridge above the intervening marshland. Rye is a substantially larger town with impressive historic remains. Its photogenic streets climb from venerable inns towards the Citadel, which contains St Mary’s Church, whose origins are Norman, and Ypres Tower, built to protect Rye and its harbour from later French raiders.

I chose to wait in Winchelsea a little longer. I ate lunch while looking over its striking, half-ruined church and contemplating the extensive wine cellars which run under the town. The sun was still high, and on Winchelsea’s Beacon Hill I dropped my bag by the remains of a mill destroyed by the Great Storm of 1987, which was once also the site of a Saxon church. I looked over the way I had come, at how the Weald comes to kneel at the sea. Then I lay with my back on the old mill stone, my mind alive to the tales I had gathered over the past two days.

]]>This article is an edited transcript of 1066: Battle of Hastings with Marc Morris, available on History Hit TV.

Harold Godwinson met Duke William of Normandy, later William the Conqueror, on a battlefield near Hastings in September 1066. The English king had just defeated Viking invaders in the north, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, and had rushed the length of the country to meet William on the battlefield in Sussex.

The first thing to say about the Battle of Hastings is that it was a very unusual face-off – a fact that contemporaries recognised. You can see it clearly on the Bayeux Tapestry, a contemporary source which shows that the English elite did not fight using cavalry.

Instead, they stood to fight in the tradition of their Anglo-Saxon predecessors and their traditional enemies, the Vikings. They drew themselves up in the famous shield wall and presented this static face to their enemy.

The Normans, since giving up being Vikings a century or so earlier, had completely embraced the Frankish mode of warfare, which was based on mounted cavalry.

The Norman elite hurtled up the hill on their horses trying to break the Saxon shield wall by throwing missiles, javelins and axes at it, but they didn’t have much effect.

The shield wall breaks

For hours, the shield wall held. Then, in what might have been a ploy, or an accident that became a ploy, the Norman line started to give way.

There was a panic on the Norman side and a rumour ran through the Norman line that William was dead.

On the Bayeux Tapestry there’s a famous scene where William takes off his helmet and rides along the line, showing his men that he’s still alive and encouraging them to follow him. William personally stopped the line from collapsing.

Whether that was a ruse or not is unclear. But, when the Anglo-Saxons up on the ridge saw that the Normans were running away, they believed that the battle was over and started running down the hill to pursue them. The Normans then wheeled around and picked off the scattered Anglo-Saxons at will.

The flight of the Normans, feigned or otherwise, compromised the integrity of the shield wall.

From that point on, the Anglo-Saxons started to become more vulnerable and gaps began to open up in the formerly impenetrable barrier.

An unusually long battle

It was also very unusual that the battle went on all day. It was a long attritional conflict, which was only ended by groups of Anglo-Saxon warriors breaking discipline and charging, getting surrounded and cut off, and finally being cut down. It was a very slow moving battle.

At that time, you would have expected such a battle to have been over in an hour or a couple of hours.

The unusual length might have been due to the fact that there were two different types of warfare clashing, but it also shows that the two sides were well matched.

There are any number of books guessing the numbers on both sides, but the truth is that we haven’t the foggiest idea of how many were fighting for either army. It is likely there were no more than 10,000 Normans, however.

That estimate is based on the numbers who fought in battles that occurred in later centuries, from which we have better evidence, such as payrolls and muster lists.Since no English king in the later Middle Ages ever managed to get more than 10,000 men across the Channel, it seems almost impossible that William the Conqueror – who was, after all, only the Duke of Normandy at that time – could have topped that figure.

There was possibly about 10,000 on both sides at the Battle of Hastings – simply based on the fact that the battle went on all day, which suggests the two armies were extremely well matched.

The shield wall’s strength was in its unity; when solid it could last all day. But once it was fractured, it became very vulnerable.

We’re told that the shield wall was compromised and that the Anglo-Saxons started to fall in greater and greater numbers. But that didn’t have to mean the end for Harold; although he would have likely lost the battle regardless at that point, the Anglo-Saxons could have started running away.

But Harold ends up dying – perhaps because he stayed and fought. His death naturally put an end to his chances of resisting William any further and cemented the Norman conquest of England.

]]>Here are 10 facts about King Harold Godwinson.

1. Harold was the son of a great Anglo-Saxon lord

Harold’s father Godwin had risen from obscurity to become the Earl of Wessex in the reign of Cnut the Great. One of the most powerful and wealthy figures of Anglo-Saxon England, Godwin was sent into exile by King Edward the Confessor in 1051, but returned 2 years later with the support of the navy.

2. He was one of 11 children

Harold had 6 brothers and 4 sisters. His sister Edith married King Edward the Confessor. Four of his brothers went on the become earls, which meant that, by 1060, all the earldoms of England but Mercia were ruled by sons of Godwin.

3. Harold became an earl himself

Harold touching two altars with the enthroned Duke looking on. Image credit: Myrabella, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Harold became Earl of East Anglia in 1045, succeeded his father as Earl of Wessex in 1053, and then added Hereford to his territories in 1058. Harold had become arguably more powerful than the King of England himself.

4. He defeated an expansionist King of Wales

He undertook a successful campaign against Gruffydd ap Llewelyn in 1063. Gruffydd was the only Welsh king ever to rule over the entire territory of Wales, and as such posed a threat to Harold’s lands in the west of England.

Gruffydd was killed after being cornered in Snowdonia.

5. Harold was shipwrecked in Normandy in 1064

There is much historical debate over what happened on this trip.

William, Duke of Normandy, later insisted that Harold had sworn an oath on holy relics that he would support William’s claim to the throne upon the death of Edward the Confessor, who was at the end of his life and childless.

However, some historians believe this story was fabricated by the Normans to legitimise their invasion of England.

6. He was elected King of England by an assembly of noblemen

13th-century version of Harold’s crowning. Image credit: Anonymus (The Life of King Edward the Confessor), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After Edward the Confessor’s death on 5 January 1066, Harold was chosen by the Witenagemot – an assembly of nobility and clergy – to be the next King of England.

His coronation in Westminster Abbey took place the very next day.

7. He was victorious at the Battle of Stamford Bridge

Harold defeated a large Viking army under the command of Harald Hardrada, after taking them by surprise. His traitorous brother Tostig, who had supported Harald’s invasion, was killed during the battle.

8. And then marched 200 miles in a week

Upon hearing that William had crossed the Channel, Harold swiftly marched his army down the length of England, reaching London by around 6 October. He would have covered around 30 miles a day on his way south.

9. Harold lost the Battle of Hastings to William the Conqueror on 14 October 1066

Harold’s death depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, reflecting the tradition that Harold was killed by an arrow in the eye. Image credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After a hard-fought battle that lasted all day, the Norman force defeated Harold’s army and the King of England lay slain on the battlefield. The Norman cavalry proved the difference – Harold’s force was made up entirely of infantry.

10. He was killed by an arrow in the eye

A figure is depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry as being killed at the Battle of Hastings by an arrow in the eye. Although some scholars dispute whether this is Harold, the writing above the figure states Harold Rex interfectus est,

]]>“Harold the King has been killed.”

William had to to secure his foothold in southern England, and required a means of ruling the rest of his new country.

As a result, from 1066 to 1087 William and the Normans built nearly 700 motte and bailey castles across England and Wales.

These castles, which were relatively quick to build, but difficult to capture, formed a key part of William’s strategy for controlling his new domain.

The origins of the motte and bailey

Popular in Europe from the 10th century, some historians emphasise the military and defensive capabilities of motte and baileys, especially in repelling Viking, Slavic and Hungarian raids into Europe.

Others explain their popularity by arguing they supported the feudal social structures of the period: they were built by feudal landowners to protect their property.

Regardless, the name ‘motte and bailey’ derives from the Norman words for ‘mound’ (motte), and ‘enclosure’ (bailey). These words describe the most important aspects of the castles’ design.

How did they build them?

The motte, or mound, on which the main keep was built was made of soil and stone. Research on Hampstead Marshall’s motte and bailey shows that it contains over 22,000 tons of soil.

The earth for the motte was piled in layers, and was capped with stone after each layer to strengthen the structure and allow faster drainage. Mottes varied in size, ranging from 25 feet to up to 80 feet in height.

A view of the Motte and Barbican at Sandal Castle. Credit: Abcdef123456 / Commons.

Ideally, the mound would have steep slopes, to prevent attackers from assaulting on foot. Additionally, a ditch would have been dug around the bottom of the motte.

The keep which stood on top of the mound was often just a simple wooden tower, but on larger mounds, complex wooden structures could be built.

The bailey, an enclosure of flattened land, lay at the bottom of the motte. It was connected to the keep on the motte by a wooden flying bridge, or by steps cut into the motte itself.

This narrow, steep approach to the keep made it easy to defend if attackers breached the bailey.

The bailey was surrounded by a wooden palisade, and a ditch (called a fosse). If it was possible, nearby streams were diverted into the ditches to produce a moat.

The outer edge of the bailey’s palisade were always within bowshot of the keep, to ward off attackers. A few baileys, like that of Lincoln Castle, even had two mottes.

The strongest mottes could take up to 24,000 man hours to build, but smaller ones could be completed in only 1,000 man hours. A motte could thus be raised in a few months, compared to a stone keep, which might take up to ten years.

From Anjou to England

The first motte-and-bailey castle was built at Vincy, Northern France, in 979. Over the following decades the Dukes of Anjou popularised the design.

William the Conqueror (then the Duke of Normandy), observing their success in neighbouring Anjou, began to build them on his Norman lands.

After he invaded England in 1066, William needed to construct castles in large numbers. They demonstrated his control of the population, ensured protection for his soldiers, and solidified his rule in remote parts of the country.

After several uprisings, William subjugated northern England in a campaign called the ‘Harrying of the North’. He then built significant numbers of motte and bailey castles to help maintain peace.

In northern England and elsewhere, William seized land from rebellious Saxon nobles and reassigned it to Norman nobles and knights. In return, they had to build a motte and bailey to protect William’s interests in the local area.

Why the motte and bailey was successful

A major factor for the success of the motte-and-bailey was that the castles could be hastily and cheaply constructed, and with local building materials. According to William of Poitiers, William the Conqueror’s chaplain, the motte and bailey at Dover was built in only eight days.

When William landed in modern-day Sussex, he had neither the time nor materials to construct a stone fortification. His castle at Hastings was eventually rebuilt in stone in 1070 after he had solidified his control over England; but in 1066 speed was the priority.

The Bayeux Tapestry depiction of Hastings castle under construction.

Also, in the more remote west and north of England, peasants could be forced to construct the castles, as the structures required little skilled labour.

Nevertheless, owing to the importance of stone structures for defensive and symbolic reasons, the motte and bailey design declined a century after William’s invasion. New stone structures could not be easily supported by mounds of earth, and concentric castles eventually became the norm.

Where can we see them today?

It is harder to find a well-preserved motte and bailey compared to other types of castles.

Predominantly made of wood and soil, many of those built under William the Conqueror decayed or collapsed over time. Others were burnt down during later conflicts, or were even converted into military defences during the Second World War.

However, many motte and baileys were converted into larger stone fortifications, or adopted into later castles and towns. Notably, at Windsor Castle, the former motte and bailey was renovated in the 19th century, and is now used as an archive for royal documents.

In Durham Castle, the stone tower on the old motte is used as student accommodation for members of the university. At Arundel Castle in West Sussex, the Norman motte and its keep now form part of a large quadrangle.

At Hastings Castle in East Sussex, close to where William the Conqueror defeated Harold Godwinson, the ruins of the stone motte and bailey still stand atop the cliffs.

Elsewhere in England, large, steep-sided mounds reveal the former presence of a motte and bailey, such as in Pulverbatch, Shropshire.

]]>Yet there was another battle that occurred on English soil that year, one that preceded both Stamford Bridge and Hastings: the Battle of Fulford, also known as the Battle of Gate Fulford.

Here are ten facts about the battle.

1. Fighting was sparked by the arrival in England of Harald Hardrada

The Norwegian king, Harald Hardrada reached the Humber estuary on 18 September 1066 with up to 12,000 men.

His aim was to take the English throne from King Harold II, arguing he should have the crown because of arrangements made between the late King Edward the Confessor and the sons of King Cnut.

2. Hardrada had a Saxon ally

Tostig, the exiled brother of King Harold II, supported Harald’s claim to the English throne and had been the one who initially convince Harald to invade.

When the Norwegian king landed in Yorkshire, Tostig reinforced him with soldiers and ships.

3. The battle occurred south of York

An image of Harald Hardrada in Lerwick Town Hall in the Shetland Islands. Credit: Colin Smith / Commons.

Although Hardrada’s ultimate aim was to gain control of the English crown, he first marched north to York, a city that was once the epicentre of Viking power in England.

Hardrada’s army, however, soon found themselves confronted by an Anglo-Saxon army just south of York on the eastern side of the Ouse River near Fulford.

4. The Anglo-Saxon army was led by two brothers

They were Earl Morcar of Northumbria and Earl Edwin of Mercia, who earlier in the year had decisively defeated Tostig. For Tostig this was round two.

The week before the battle, Morcar and Edwin hastily gathered together an army to confront Hardrada’s invasion force. At Fulford they fielded some 5,000 men.

5. Morcar and Edwin occupied a strong defensive position…

Their right flank was protected by the River Ouse, while their left flank was protected by ground too swampy for an army to march through.

The Saxons also had a formidable defence to their front: a stream three metres wide and one metre deep, that the Vikings would have to cross if they were to reach York.

Swampland by the River Ouse south of York. Similar land protected the Saxon’s left flank at Fulford. Credit: Geographbot / Commons.

6. …but this soon worked against them

Initially only Harald and a small portion of his army arrived at the battlefield facing Morcar and Edwin’s army as most of Harald’s men were still some distance away. Thus for a time the Anglo-Saxon army outnumbered their foe.

Morcar and Edwin knew that this was a golden opportunity to attack but the River Ouse’s tide was then at its highest and the stream in front of them was flooded.

Unable to advance, Morcar and Edwin were forced to delay their attack, watching with frustration as more and more of Harald’s troops began to assemble on the far side of the stream.

7. The defenders struck first

At around midday on 20 September 1066 the tide finally receded. Still bent on attacking their foe before the full might of Harald’s force could arrive, Morcar then led an attack on Harald’s right flank.

After a melee in the marshlands, Morcar’s Saxons began to push Hardrada’s right flank back, but the advance soon petered out and came to a standstill.

8. Harald gave the decisive order

He pushed forwards his best men against Edwin’s Saxon soldiers stationed nearest the Ouse River, quickly overwhelming and routing that wing of the Saxon army.

As a small hill ensured Edwin’s force was not within sight of them, Morcar and his men probably did not realise their right wing had collapsed until it was too late.

Harald’s best men routed the right flank of the Saxon army. Credit: Wolfmann / Commons.

9. The Vikings then surrounded the remaining English

Having chased Edwin’s men away from the riverbank, Harald and his veterans now charged the rear of Morcar’s already engaged men. Outnumbered and outmanoeuvred, Morcar sounded the retreat.

The English lost nearly 1,000 men although both Morcar and Edwin survived. It did not come without cost for the Vikings however as they too had lost a similar number of men, presumably mostly against Morcar’s forces.

10. Hardrada did not have long to savour his victory at Fulford

After Fulford York surrendered to Harald and ‘the Last Viking’ prepared to march south. He didn’t need to, however, as barely five days after Fulford, he and his army were attacked by Harold Godwinson and his army at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.

]]>He was the son of the about-to-be duke of Normandy, Robert. But he was the product of Robert’s liaison with a woman of fairly humble origins from the town of Falaise called Herleva. Despite this, however, Herleva was treated honourably and so was William. The assumption was likely that Robert might go on to marry a more church-sanctioned match with whom he would produce other children.

This article is an edited transcript of William: Conqueror, Bastard, Both? with Dr Marc Morris on Dan Snow’s History Hit, first broadcast 23 September 2016.

But what surprised everybody at Christmas in 1034, when William was still a little boy of six or seven, was that his dad decided to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem from which he never came back. And before he went off to the Holy Land, Robert took the precaution of getting the nobles of Normandy to swear an oath that they would accept William in the event that he didn’t return.

A state of Richard the Good, as William’s father was known, in Falaise town square. Credit: Michael Shea –imars / Commons

And so that’s what happened when the news came back from Nicea in 1035 that Robert had perished in the sands of the Middle East – the nobles accepted the illegitimate boy William as their new duke.

The problem with having a child on the throne

William’s illegitimacy wasn’t particularly a problem because the Normans were originally Vikings and the Vikings had traditionally been pagan. The Normans themselves were considerably more civilised than their Viking ancestors by 1035, but they were not particularly hung up on the idea of a church wedding.

But although William’s illegitimacy wasn’t a huge problem, his age was. In a warrior society in the early 11th century, having a child on the throne was a recipe for disaster. Lots of people who had ancient grudges with their neighbours took advantage of William being on the throne and took authority into their own hands.

So, very quickly, society in Normandy went to hell in a handcart and there were fires and rebellions all over the duchy.

One of the problems of that period is that contemporary sources aren’t that great; the very detailed ones are from about 100 years after the event. But we’re told that William was sleeping in his chamber in Normandy when his steward was murdered – had his throat cut – in the same chamber.

The question mark is whether William’s own life was actually in danger? Whether those who killed his steward were also planning to kill and replace him? Or whether it was simply factional fighting, an attempt to replace the people around William? It was probably the latter because if someone had wanted to take a seven-year-old boy in those circumstances then they wouldn’t have had a problem.

So, the people who were killed in that period were William’s protectors and guardians and they were replaced by their rivals who crop up in the very next charter or source as the people running the show.

But although William himself wasn’t killed, it would certainly have been a very frightening time for a seven or eight-year-old boy.

A young William takes charge

In any period of history like that, it suits some people when law and order breaks down or when established authority breaks down because people with ancient grievances can settle them themselves. So it suits men with strong right arms and twitchy swords. But the majority of people would have lamented the breakdown of order.

What ultimately righted the situation was William taking personal charge. We’re told he was knighted at a young age – around 15. That is pretty young but not impossibly young, and once he had been knighted it signified that he had come of age and was able to sort of wield the sword in his own right.

He was also associating by that age with other young men, other Norman nobles and magnates, who were his kind of boon companions throughout the rest of his life.

But although what turned the situation in Normandy around was William asserting his personal authority from the mid-1040s, the forces that arranged against him didn’t go down without a fight.

At the start of 1047, it looked like he was facing his biggest danger to date – there seems to have been a genuine attempt to replace him, a rebellion that broke out in the west of Normandy. It was sufficiently serious that William ran away to France to seek the help of his overlord, the French King Henry I.

The king obliged William and the two sides came to battle in a place near Caen called Val-es-Dunes. William was still only in his late teens at that point, but he was successful and so vindicated his right to rule.

Looking beyond Normandy

What William did in the first instance in terms of looking elsewhere, beyond Normandy, was to look elsewhere for a bride and he got married to the daughter of the Count of Flanders, Matilda. She was about the same age as William, just a little bit younger. But at that point he wasn’t starting to look with an acquisitive eye at other territory.

A statue of Matilda of Flanders in Paris. Credit: Tom Hilton / Commons

Throughout the next 10, 15 years of William’s career, he was on the defensive. Normandy was invaded by the Count of Anjou to the south, and William also fell out with the King of France, the man who’d come to his rescue in 1047.

But although Normandy was under threat for most of the 1050s, the crucial turning point in William’s career came in the year 1051 when he was invited to England.

That is something that has been debated in the 20th century, but it seems absolutely clear from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that William crossed the channel in 1051 to visit his second cousin King Edward the Confessor.

Apparently, that was the point at which William was promised the English throne by Edward upon his death. That obviously marked the seed being sown for the Norman conquest of England 15 years later. It’s entirely possible that that development is what caused the other magnates of France, particularly the king, to turn against William in the 1050s.

As a result, although William is set up to perhaps inherit England in 1051, for most of the decade that followed he was on the defensive and trying to protect Normandy’s borders rather than trying to enlarge them.

The problem with William is that, to some extent, we’re well informed about his activities because we have a contemporary biography written of him by his chaplain William of Poitier.

But because it was written for William or at least for William’s court, by a very sycophantic biographer, we only get this strident propagandist description of William’s “wonderful personality” and “wonderful achievements”.

What William of Poitier doesn’t tell us is why the King of France and the Count of Anjou and others turned against him.

But certainly in terms of the political balance of that part of the world, the notion that the Duke of Normandy and the King of England might be one and the same person at some point in the future would have been deeply worrying. So you can see why some people would have wanted to remove William before that happened.

William’s relentlessness

Despite the unreliability of William’s biographer, his reputation as an extraordinary leader is borne out by the way his career unfolded. We know that he was successful in battle in 1047, we know that he was successful in battle in 1066.

One of the key things that leaps out at you while going over the sources is William’s relentlessness. Relentlessness or words to that effect are used by both William’s Norman biographer and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

There’s a telling line that says, “He was too relentlessness to care, even though everyone might hate him”. He’s almost got an ideological streak that says “God is on my side, I’m right. I’m going to do this, no matter what anybody says”.

So whether it was leading troops through the frozen wastes of northern England in 1069, 1070 when all of his soldiery were deserting, or chancing all at Hastings, he was prepared to take risks.

The thing about the Battle of Hastings and the Norman invasion of 1066 that people tend to forget is that it was very likely to have ended the other way around. Most of the risk was with William – he had to get all of his horses and ships of men across the channel. He was the one sailing into adverse weather. It was an incredibly, insanely risky undertaking.

You don’t do that kind of thing unless you think God is on your side. Unless you think that you will be vindicated when swords are drawn. And that seem to be the most striking thing about his personality – the belief that God was on his side, as well as the relentlessness driving him on.

]]>This article is an edited transcript of William: Conqueror, Bastard, Both? with Dr Marc Morris on Dan Snow’s History Hit, first broadcast 23 September 2016. You can listen to the full episode below or to the full podcast for free on Acast.

William the Conqueror started his reign of England by professing to want continuity. There’s a very early writ, now preserved in the London Metropolitan Archives, that was put out by William within months, if not days, of his coronation on Christmas Day in 1066, essentially saying to the citizens of London: your laws and customs will be exactly as they were under Edward the Confessor; nothing’s going to change.

So that was the stated policy at the top of William’s reign. And yet, massive change followed and the Anglo-Saxons weren’t happy about it. As a result, the first five or six years of William’s reign were ones of more or less continuing violence, continuing insurgency and, then, Norman repression.

What made William different from the foreign rulers who came before him?

The Anglo-Saxons had coped with various rulers during the medieval period who had come over to England from abroad. So what was it about William and the Normans that led the English to keep rebelling?

One major reason was that, after the Norman conquest, William had an army of 7,000 or so men at his back who were hungry for reward in the form of land. Now the Vikings, by contrast, had generally been happier to just take the shiny stuff and go home. They weren’t determined to settle. Some of them did but the majority were happy to go home.

William’s continental followers, meanwhile, wanted to be rewarded with estates in England.

So, from the off, he was having to disinherit Englishmen (Anglo-Saxons). Initially dead Englishmen, but, increasingly, as the rebellions against him went on, living Englishmen too. And so more and more Englishmen found themselves without a stake in society.

That led to great change within English society because, ultimately, it meant that the entire elite of Anglo-Saxon England was disinherited and replaced by continental newcomers. And that process took several years.

Not a proper conquest

The other reason for the constant rebellions against William – and this is the surprising bit – is that he and the Normans were initially perceived by the English as being lenient. Now, that sounds strange after the bloodbath that was the Battle of Hastings.

But after that battle was won and William had been crowned king, he sold the surviving English elite back their lands and tried to make peace with them.

At the start he tried to have a genuinely Anglo-Norman society. But if you compare that to the way that the Danish king Cnut the Great started his reign, it was very different. In the traditional Viking manner, Cnut went around and if he saw someone who was a potential threat to his rule then he just executed them.

With the Vikings, you knew you had been conquered – it felt like a proper Game of Thrones-style conquest – whereas I think people in Anglo-Saxon England in 1067 and 1068 thought that the Norman conquest was different.

They might have lost the Battle of Hastings and William might have thought he was king, but the Anglo-Saxon elite still thought they were “in” – that they still had their lands and their power structures – and that, come the summer, with one big rebellion, they would get rid of the Normans.

So because they thought they knew what a conquest felt like, like a Viking conquest, they didn’t feel like they had been properly conquered by the Normans. And they kept rebelling from one year to the next for the first several years of William’s reign in the hope of undoing the Norman conquest.

William turns to brutality

The constant rebellions resulted in William’s methods for dealing with opposition to his rule ultimately becoming even more savage than those of his Viking predecessors.

The most notable example was the “Harrying of the North” which really did put an end to the rebellion against William in the north of England, but only as a result of him more or less exterminating every living thing north of the River Humber.

The Harrying was William’s third trip to the north in as many years. He went north the first time in 1068 to quell a rebellion in York. While there he founded York Castle, as well as half a dozen other castles, and the English submitted.

The remains of Baile Hill, believed to be the second motte-and-bailey castle built by William in York.

At the start of the following year, there was another rebellion and he returned from Normandy and built a second castle in York. And then, in the summer of 1069, there was another rebellion – that time supported by an invasion from Denmark.

At that point, it really did look as though the Norman conquest was hanging in the balance. William realised that he could not hang onto the north simply by planting castles there with small garrisons. So, what was the solution?

The brutal solution was that if he couldn’t hold the north then he would make damn sure that no one else could hold it.

So he devastated Yorkshire, literally sending his troops over the landscape and burning down barns and slaughtering cattle etc so that it could not support life – so that it could not support an invading Viking army in the future.

People make the mistake of thinking that it was a new form of warfare. It wasn’t. Harrying was a perfectly normal form of medieval warfare. But the scale of what William did in 1069 and 1070 did strike contemporaries as way, way over the top. And we know that tens of thousands of people died as a result of the famine that followed.

]]>This article is an edited transcript of William: Conqueror, Bastard, Both? with Dr Marc Morris on Dan Snow’s History Hit, first broadcast 23 September 2016. You can listen to the full episode below or to the full podcast for free on Acast.

William the Conqueror is very hard to empathise with. His counterinsurgencies to put down the many rebellions in England that followed the Norman conquest make him sound like a sort of sadistic maniac.

Despite this, we were always told for the last 60 or so years that, when William died in 1087, some people at his funeral remembered some very surprising qualities about him. He was cheerful, he was eloquent, he was affable, they said – so there was apparently this other side to his character, which you might not necessarily associate with the brutal conqueror.

However, that was actually the result of Hugh of Flavigny’s Chronicle having been mistranslated – all those positive adjectives were actually about the Abbot of Verdun. So, we no longer have any really good evidence for a cheerful, affable William the Conqueror.

William’s English obituary writer

Having said all that, it’s still useful to look at what was said about William by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle because one of the very best sources for the Norman king’s reign and character is his obituary in the Chronicle.

One, because it’s long and detailed but, two, because it was written by an anonymous Englishman – it’s written in Old English – who says he lived at William’s court and saw him with his own eyes. So it’s written from the point of view of the conquered.

As you’d expect, this writer says there are certain good things about William’s rule, that he kept good order and he feared God and those kinds of things. And he built an abbey at Battle, the site of the Battle of Hastings. He also lays into William for the bad things, however.

He says he was greedy, that he extracted way too much gold, and that he built far more castles than was necessary.

That’s another crime against him, because William commanded hundreds of castles to be built in the 20 odd years of his reign.

The writer also condemns him for introducing the Royal Forest. So, there are lots of things that the Chronicle gets exercised about. But the surprising thing is that he doesn’t accuse William of being cruel, a chant that is often laid at William’s door by modern historians – that he was a cruel, savage man, because he chopped people’s hands or feet off.

Hands and feet but not heads

So we have this silence from the Chronicle regarding William being cruel or savage. The thing is, William did do all those things – he did chop off people’s hands and feet if they rebelled against him. But that was true of every other 11th-century warrior or warrior king.

That is the way that people did politics and warfare in the mid-11th century. If you look at the Vikings or the Anglo-Saxons before 1066 they’re doing exactly the same thing, if not worse.

William may have had people’s hands and feet chopped off, but not their heads.

The interesting thing about William is that we’re told he locked up his prisoners for a long time and kept people in prison forever and ever and ever. And again, modern historians have said that that shows what a cruel man he was, but the alternative to locking people up is chopping their heads off.

What differentiated William from earlier kings of England and, indeed, other rulers in the Anglo-Saxon or Viking worlds is that he didn’t chop people’s heads off – almost without exception.

He didn’t execute his political enemies in the way that Viking and Anglo-Saxon rulers prior to the Norman conquest of England in 1066 had done as a matter of routine.

So there have been arguments around for about a quarter of a century now suggesting that William was the king who introduced chivalry to England. At the same time as there were rebellions kicking off everywhere in England following the Norman conquest, with hundreds of thousands of people being killed, the way that the English did politics at the highest level changed as a result of William’s rule.

It meant that if people were captured or surrendered then they were not executed; instead, they were imprisoned or held for ransom, and, maybe, one day further down the line, even released.

William’s legacy today

His legacy during his lifetime and after his death was obviously one of extreme violence and upheaval and disruption. People also noticed every major church being rebuilt, as well the building of hundreds of new castles. So the physical appearance of England was drastically changed by William.

But 950 years on, very few of those consequences are so apparent. The thing we live with today that is a direct result of William and the Norman conquest, of course, is the language we’re speaking now, which is a mongrel tongue of English and Norman, Norman-French.

]]>This article is an edited transcript of 1066: Battle of Hastings with Marc Morris, available on History Hit TV.

The year 1066 saw several candidates emerge as rivals for the English crown. Having defeated the Vikings at Stamford Bridge, King Harold Godwinson journeyed south very quickly to respond to the new Norman threat that had landed on the south coast.

Harold could have travelled 200 odd miles from York to London in around three or four days at that time. If you were the king and you travelled with a mounted elite, you could ride hell-for-leather if you needed to get somewhere quick, and the horses could be replaced.

Whilst he was doing that, Harold would have had other messengers riding out into the provinces, proclaiming a new muster in London in 10 days’ time.

Should Harold have waited?

What we’re told by several sources about Harold is that he was too hasty. Both English and Norman chronicles tell us that Harold set out for Sussex and William’s camp too soon, before all his troops had been drawn up. That fits with the idea that he disbanded his troops in Yorkshire. It wasn’t a forced march south for the infantry; it was instead a gallop for the king’s elite.

Harold would likely have done better to wait rather than to rush down into Sussex with fewer infantry than might have been ideal.

He would have had more troops if he had waited a bit longer for the muster, which involved counties sending their reserve militiamen to join Harold’s army.

The other thing to note is that the longer Harold waited, the more likely he was to gain more support from Englishmen who didn’t want to see their farms put to the torch.

Harold could have played a patriotic card, positing himself as a king of England protecting his people from these invaders. The longer the prelude to battle went on, the greater the danger for William’s position, because the Norman duke and his army had only brought a certain amount of supplies with them.

Once the Normans’ food ran out, William would have had to start breaking up his force and going out to forage and ravage. His army would have ended up with all the disadvantages of a being an invader living off the land. It would have been much better for Harold to wait.

William’s invasion plan

William’s strategy was to loot and sack settlements in Sussex in an attempt to provoke Harold. Harold was not only a crowned king but a popular one too, which meant he could afford a draw. As a 17th-century quote from the Earl of Manchester, about the Parliamentarians versus the Royalists, says:

“If we fight 100 times and beat him 99 he will be king still, but if he beats us but once, or the last time, we shall be hanged, we shall lose our estates, and our posterities be undone.”

If Harold was defeated by William but managed to survive, he could have headed west and then regrouped to fight another day. That exact thing had happened 50 years earlier with the Anglo-Saxons versus the Vikings. Edmund Ironside and Cnut went at it about four or five times until Cnut eventually won.

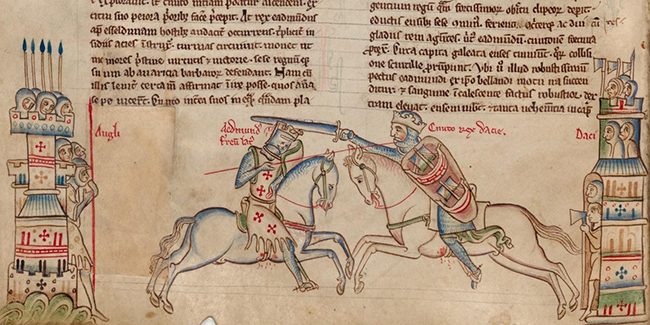

This illustration depicts Edmund Ironside (left) and Cnut (right), fighting one another.

All Harold had to do was not die, whereas William was gambling everything. For him, it was the biggest roll of the dice of his career. It had to be a decapitation strategy. He wasn’t coming over to plunder; it wasn’t a Viking raid, it was a play for the crown.

The only way William was going to get the crown was if Harold obliged him by coming to battle early and dying.

William thus spent time harrying Sussex to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of Harold’s lordship, and Harold rose to the bait.

Harold’s defence of England

Harold used the element of surprise against the Vikings to win his decisive victory in the north. He rushed up to Yorkshire, secured good intelligence on their location and caught them unawares at Stamford Bridge.

So surprise worked well for Harold in the north, and he attempted a similar trick against William. He tried to hit William’s camp at night before the Normans realised he was there. But it didn’t work.

Hardrada and Tostig were completely caught with their pants down at Stamford Bridge. That’s literally the case in terms of dress, because we’re told by an 11th-century source that it was a hot day and so they had gone from York to Stamford Bridge without their armour or their mail shirts, putting them at a massive disadvantage.

Hardrada really dropped his guard. Harold and William, on the other hand, were probably equally matched in their generalship.

William’s reconnoitring and his intelligence were better than Harold’s, however; we’re told that the Norman duke’s knights reported back to him and warned him of the impending night attack. William’s soldiers then stood guard throughout the night in expectation of an attack.

When an attack didn’t come, they set off in search of Harold and in the direction of his camp.

The site of the battle

The tables were turned and instead it was William who caught Harold unawares rather than the other way round. The place he met Harold at the time didn’t have a name. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says they meet at the grey apple tree, but nowadays we call that place “Battle”.

There has been some controversy in recent years about the site of the battle. Lately, there has been a suggestion that the only evidence that the monastery, Battle Abbey, was placed on the site of the Battle of Hastings, is the Chronicle of Battle Abbey itself, which was written more than a century after the event.

But that isn’t true.

There are at least half a dozen earlier sources that say William built an abbey on the site where the battle was fought.

The earliest of them is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in William’s obituary for the year 1087.

The Englishman who wrote it says that William was a great king who did many dreadful things. He writes that of the good things he did, he ordered an abbey to be built on the very spot where God granted him victory over the English.

So we have a contemporary voice from the time of William the Conqueror, an English voice from his court, that says the abbey is situated where the battle was fought. It’s as solid evidence as we will find for this period.

One of the most titanic, climactic battles in British history, saw Harold begin in a very good defensive position, anchored to a large slope, blocking the road to London.

Harold had the high ground. Everything from Star Wars onwards tells us that if you’ve got the high ground, you’ve got a better chance. But the issue with Harold’s position is that it was too narrow. He couldn’t deploy all of his men. Neither commander had an ideal position. And that’s probably why the battle descended into a long, drawn-out melee.

]]>This article is an edited transcript of 1066: Battle of Hastings with Marc Morris, available on History Hit TV.

The first reason why the Norman invasion resulted in such significant changes for English society was because it succeeded. That reason isn’t axiomatic. Harold could have made any invasion far more difficult for William, because all he had to do was not die; he could have just retreated.

It wouldn’t have been great for his self-image, but he could have easily sounded the retreat at the Battle of Hastings, disappeared into the woods, and regrouped a week later. Harold was a popular ruler, and he could probably have coped with a small blow to his reputation. But what absolutely signalled the end for Harold’s reign, of course, was his death.

The death of Harold

On what finally caused Harold’s death, the answer is: we don’t know. We can’t possibly know.

All you can say is that, in recent years, the arrow story – that Harold died after getting an arrow lodged in his eye – has been more or less totally discredited.

It’s not to say it couldn’t have happened because there were tens of thousands of arrows being loosed that day by the Normans.

The portion of the Bayeux Tapestry that depicts Harold (second from left) with an arrow lodged in his eye.

It is fairly probable that Harold might have been injured by an arrow, but the only contemporary source that shows him with an arrow in the eye is the Bayeux Tapestry, which is compromised for any number of reasons – either because it was heavily restored in the 19th century or because it is an artistic source that copies other artistic sources.

It is too technical an argument to go into here, but it looks like the death scene for Harold from the Bayeux Tapestry is one of those occasions where the artist is borrowing from another artistic source – in this case, a biblical story.

The destruction of the aristocracy

It boils down to the fact that not only does Harold get killed at Hastings, but his brothers and many other elite Englishmen – who constituted a core of English aristocrats – also die.

In the years that followed, in spite of William’s professed intention to have an Anglo-Norman society, the English continued to rebel to try and undo the conquest.

These English rebellions generated more and more Norman repression, culminating famously with a series of campaigns by William known as the “Harrying of the North”.

But as devastating as all this was to the general populace, the Norman conquest was particularly devastating to the Anglo-Saxon elite.

If you look at the Domesday Book, famously compiled the year before William died in 1086, and take the top 500 people in 1086, only 13 of the names are English.

Even if you take the top 7,000 or 8,000, only about 10 per cent of them are English.

The English elite, and I’m using the elite in a very broad sense here, since I’m talking about 8,000 or 9,000 people, have been largely replaced.

They have been replaced to the point where, nine times out of 10, the lord in every single English village or manor is a continental newcomer speaking a different language, and with different ideas in his head about society, the way that society should be regulated, about warfare, and about castles.

Different ideas

Castles are introduced as a result of the Norman Conquest. England had about six castles prior to 1066, but by the time William died it has several hundred.

The Normans also had different ideas about architecture.

They ripped down most of the Anglo-Saxon abbeys and cathedrals and replaced them with huge, new Romanesque models. They even had different attitudes towards human life.

The Normans were absolutely brutal in their warfare, and they rejoiced in their reputation as masters of war. But at the same time, they couldn’t abide slavery.

Within a generation or two of the conquest, the 15 to 20 per cent of English society who had been kept as slaves were liberated.

On all kinds of levels, as a result of the replacement, complete replacement or almost complete replacement of one elite by another, England was changed forever. In fact, it may have been the biggest change that England has ever experienced.

]]>