When the British Empire declared war against the Kingdom of Zululand in January 1879, many believed the war was a foregone conclusion. At the time Britain controlled the largest empire the world had ever seen and they were facing an enemy trained in tactics very similar to those of an ancient Roman legion.

Yet things soon went terribly wrong. On 22 January 1879 a British force stationed next to a hill called Isandlwana found themselves opposed by some 20,000 Zulu warriors, well-versed in the art of war and under orders to show no mercy. What followed was a bloodbath.

Here are 12 facts about the Battle of Isandlwana.

Watch Now

Watch Now1. Lord Chelmsford invaded Zululand with a British army on 11 January

Lord Chelmsford.

The invasion came after Cetshwayo, the king of the Zulu Kingdom, did not reply to an unacceptable British ultimatum that demanded (among other things) he disband his 35,000-strong army.

Chelmsford thus led a 12,000-strong army – divided into three columns – into Zululand, despite having received no authorisation from Parliament. It was a land grab.

2. Chelmsford made a fundamental tactical error

Confident that his modernised army could easily quash Cetshwayo’s technologically inferior forces, Chelmsford was more worried that the Zulus would avoid fighting him on the open field.

He therefore divided his central column (that consisted of over 4,000 men) in two, leading the majority of his army towards where he believed he would find the main Zulu army: at Ulundi.

3. 1,300 men were left to defend Isandlwana…

Half of this number were either native auxiliaries or European colonial troops; the other half were from British battalions. Chelmsford placed these men under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Pulleine.

4. …but the camp was not suited for defence

Isandlwana Hill today, with a white cairn in the foreground highlighting a British mass grave.

Chelmsford and his staff decided not to erect any substantial defences for Isandlwana, not even a defensive circle of wagons.

5. The Zulus then sprung their trap

At around 11am on 22 January a British Native Horse contingent discovered some 20,000 Zulus hidden in a valley within seven miles of the lightly-defended British camp. The Zulus had completely outmanoeuvred their foe.

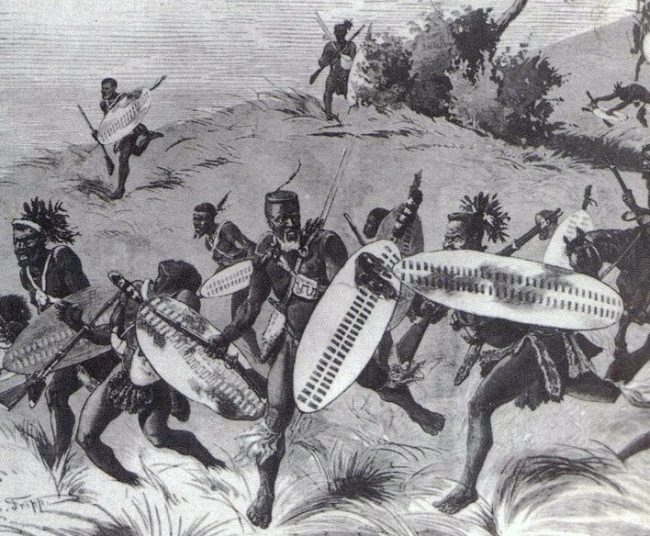

Zulu warriors. They were organised into regiments called ‘Impis’.

6. The Zulus were discovered by Zikhali’s Native Horse contingent

Their discovery prevented the camp from being taken by complete surprise.

7. The British battalions resisted for over an hour…

Despite the limited defences, the British soldiers – equipped with the powerful Martini-Henry rifle – stood their ground, firing volley after volley of bullets into the approaching Zulus until their ammunition ran low.

8. …but the Zulus ultimately overwhelmed the British camp

Only a part of the Zulu army was attacking the British camp head on. At the same time, another Zulu force was outflanking the British right wing – part of their famous buffalo horns formation, designed to encircle and pin the enemy.

After this separate Zulu force had successfully outmanoeuvred the British, Pulleine and his men found themselves attacked on multiple sides. Casualties began to mount rapidly.

Watch Now

Watch Now9. It was one of the worst defeat ever suffered by a modern army against a technologically inferior indigenous force

By the end of the day, hundreds of British redcoats lay dead on the slope of Isandlwana – Cetshwayo having ordered his warriors to show them no mercy. The Zulu attackers also suffered – they lost somewhere between 1,000 and 2,500 men.

Today memorials commemorating the fallen on both sides are visible at the site of the battlefield, beneath Isandlwana Hill.

10. The story goes that an attempt was made to save the Colour…

The story goes that two Lieutenants – Nevill Coghill and Teignmouth Melville – attempted to save the Queen’s Colour of the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment. As they were trying to cross the Buffalo River, however, Coghill lost the Colour in the current. It would be discovered ten days later further downstream and now hangs in Brecon Cathedral.

As for Coghill and Melville, according to the story battered and bruised they reached the far bank of the Buffalo River where they made their final stand. Both were posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions and their heroic tale reached mythic proportions back home, resulting in it being relayed in various paintings and artwork.

A painting of Coghill and Melville attempting to save the Queen’s Colour of the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment. The painting was done by French artist Alphonse de Neuville in 1880 – one year after the battle.

11…but not everyone viewed Coghill and Melville as heroes

In his South African journal, British commander Garnet Wolseley stated,

“I don’t like the idea of officers escaping on horseback when their men on foot are being killed.”

Some witnesses claim that Coghill and Melville fled Isandlwana out of cowardice, not to save the colours.

12. Contemporary British Imperialist poetry described the disaster as the British Thermopylae

Paintings, poetry and newspaper reports all emphasised the valiant British soldier fighting to the end in their desire to show Imperial heroism at the battle (the 19th century was a time when Imperialist thinking was very visible within British society).

Albert Bencke’s poem, for example, highlighted the deaths of the soldiers stating,

‘Death they could not but foreknow

Yet to save their country’s honour

Died, their faces to the foe.

Yea so long a time may be

Purest glory shall illumine

“Twenty-fourth’s” Thermopylae!’

The official portrayal of this defeat in Britain thus attempted to glorify the disaster with tales of heroism and valour.

Albert Bencke attempted to compare the British last stand at Isandlwana to the Spartan last stand at Thermopylae.