Love him or loathe him, Perdiccas was bold. The former lieutenant of Alexander the Great was brutal, scheming, and audacious.

In the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s death, Perdiccas assumed the most powerful position in the empire through means of murder and compromise. He had assumed the role of prostates (regent), and controlled the two puppet kings: Arrhidaeus III, Alexander’s elder half-brother, and Alexander IV, the infant son of Alexander the Great.

An over-powerful regent

By the start of 321 BC the regent’s power was immense. Fresh from military victories both in Cappadocia and against rebel montane tribesmen who inhabited the highlands near the western edge of the Taurus Mountains, Perdiccas’ control over the royal army was seemingly incontestable.

The victories he gained and the loot he spread among his men earned him their respect and trust. All soldiers love a winner. None more so than Alexander‘s glorified veterans, equipped with ornate armour and fuelled with a Macedonian élan for military success.

Watch Now

Watch NowPerdiccas’ control of the world’s most formidable fighting force made him powerful. Filled with ambition and confidence, he started to advance his own imperial ambitions. He wanted the throne.

Throughout 321 BC, Perdiccas, his brother Alcetas and his ally Eumenes all had ambitions to see the regent remove contentious figures and, in time, assume the kingship. They devised a plan.

Possessing royalty

A royal marriage to Cleopatra, Alexander the Great’s only full sister, presented itself to Perdiccas in 321 BC. Initially Perdiccas, with advice from his brother Alcetas, decided to ‘postpone’ the offer. They wanted to prevent any suspicion of the regent’s great imperial ambitions arising among the powerful officials in Europe (Antipater and Craterus) before they were ready (Perdiccas’ ally Eumenes had advised Perdiccas to marry Cleopatra straight away).

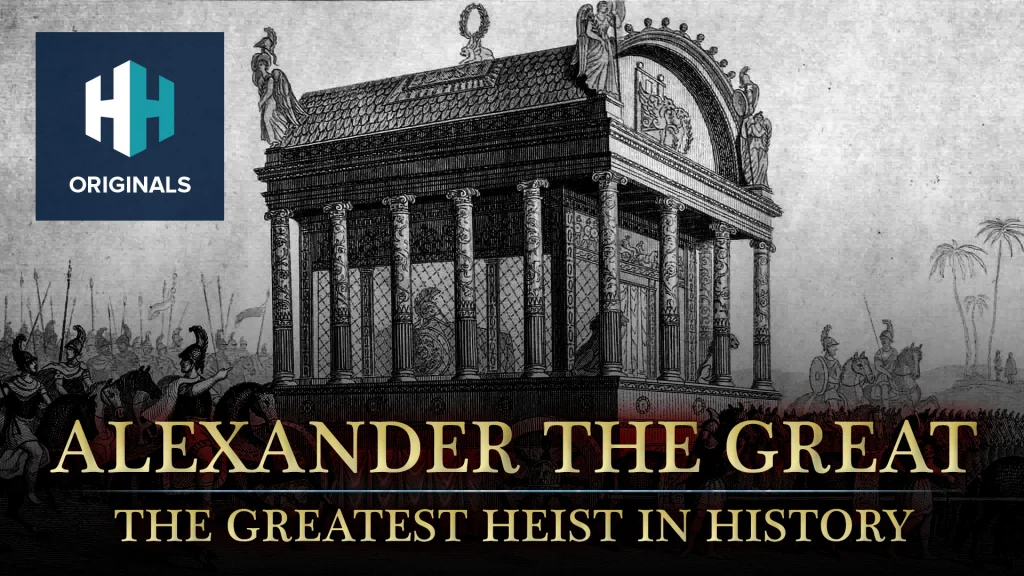

It is plausible that both Perdiccas and Alcetas had every intention that the former should marry Cleopatra, but only when all the necessary pieces were in place. The events they were awaiting are unclear. The historian Edward Anson argues it may have been Antipater’s death – the man was aged about 80 at the time. But more likely is that they were awaiting the arrival in Asia Minor of Alexander the Great’s elaborate funeral carriage. This golden mini-temple on wheels was at that moment conveying the dead king’s body west from Babylon.

An impression of Alexander’s funeral procession

Image Credit: PRISMA ARCHIVO / Alamy Stock Photo

Once Perdiccas had this powerful talisman in his possession, he could set forth for Macedonia and initiate a great plan. En-route he would divorce Nicaea, daughter of the statesman Antipater, and wed Cleopatra. The marriage alliance with Antipater would be ruthlessly nullified, but by then Perdiccas would be too powerful for the viceroy to confront him.

Invincible

Picture the scene. Perdiccas would have had himself arriving in ancient Macedonia as the husband of Alexander the Great’s full sister, greeted by the conqueror’s mother as his own mother-in-law. He would be the man who had dutifully conveyed Alexander’s divine corpse and its elaborate funeral carriage back to Macedonia. The two kings, the royal army and, not to mention, Alexander the Great’s Bactrian wife Roxana, would also be in the regent’s entourage.

With these powerful symbols of authority under his control, and presenting himself as the heir of Alexander’s empire, Perdiccas would have appeared all-but unassailable. Antipater and Craterus, though themselves highly-revered in their own right as generals of Alexander, would have been unable to contest Perdiccas’ position.

By late 321 BC, everything seemed to be on track. The killing of Alexander the Great’s ‘Amazonian’ half-sister Cynane by Alcetas was inconvenient, but perhaps regarded as necessary to ensure Perdiccas’ continued control over the kings.

Ancient Alexander’s Sarcophagus Detail, Istanbul.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

In the grand scheme of things, the killing did not derail Perdiccas’ grand plans. Cynane’s death had not affected Cleopatra. She had remained nearby, seemingly awaiting Perdiccas’ official offer of marriage. Meanwhile the funeral cart was on its way west. As soon as it reached the regent in Pisidia, then he could return with it to Macedon with supreme power.

The body snatch

But then: disaster! Ptolemy, who became ruler of Egypt (323–285 BC) in the wake of Alexander’s death, seized Alexander’s funeral cart en-route in one of history’s most significant and successful heists. In one fell swoop, Ptolemy had pulled the rug out from under Perdiccas and his carefully-crafted grand plan.

In hindsight, wouldn’t Perdiccas have prepared for such an act from an increasingly-dissident Ptolemy? Surely the regent should have ensured that the carriage was greeted by his own men as it reached Syria’s eastern borders, given its invaluable cargo? For whatever reason, he didn’t. The body was hijacked and Perdiccas’ great plan came crashing down. What followed would, ultimately, send the empire spiralling into the First War of the Successors, culminating in Perdiccas’ miserable demise.

What if Perdiccas had foiled Ptolemy’s heist of the funeral carriage? And what if Alexander‘s corpse had remained in Perdiccas’ possession? Would he have seen through his grand plan and become Alexander’s true successor? He certainly would have had the tools to accomplish it. Whether he would have succeeded and whether he would have maintained control, however, are two different questions.