Oliver Cromwell remains one of the most divisive figures in British history: some hail him as a champion of democracy and radical revolutionary, whilst others label him as a Puritan killjoy who oversaw the execution of the king.

Whatever your opinion, Cromwell overturned years of established order in England and oversaw a pivotal period in English history and his legacy has been far-reaching. Here are 10 facts about the England’s first Lord Protector.

1. He was distantly related to Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister

Oliver Cromwell was born in Huntingdon to a family in the landed gentry. His great-great-grandmother, Katherine, was Thomas Cromwell‘s older sister, and her sons chose to take her name, Cromwell, rather than their father’s.

Oliver was one of 10 children, and the only boy to survive infancy.

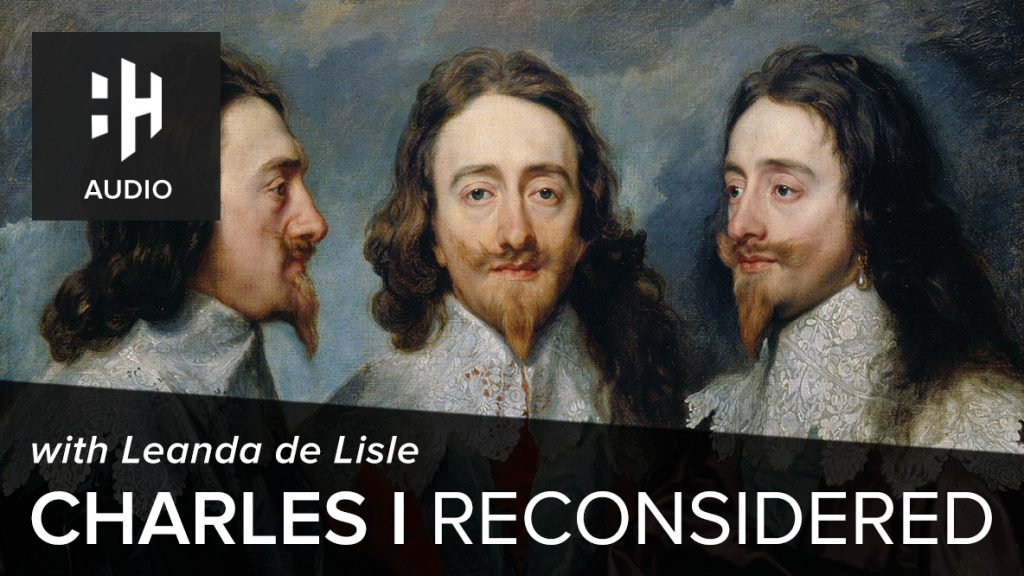

Thomas Cromwell by Hans Holbein the Younger

Image Credit: Public Domain

2. Relatively little is known about the first 40 years of his life

For a man who would become so prominent in public life, Cromwell’s early years remain relatively obscure. He studied at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, and it’s thought that he studied at Lincoln’s Inn after this, but there is no recorded evidence of this fact.

Aged 21, Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier, the daughter of a London leather merchant who had Puritan connections: the pair went on to have 9 children. Whilst the marriage appears to have been loyal and affectionate, it also brought plenty of connections which served the ambitious Cromwell well in his career.

3. He had something of a crisis of faith

Whilst Cromwell was certainly exposed to Puritanism from early on, it seems that in the 1620s he had something of a personal crisis. Despite his successful election as an MP for Huntingdon in 1628, records show he sought treatment for a variety of issues, including depression, in the same year.

In 1629, Charles dismissed Parliament: he would not call it again for 11 years. In the meantime, it seems Cromwell had a spiritual awakening. His letters began to use increasingly Puritanical language, speak of more radical beliefs and include more Biblical references and quotations than ever before. He even tried to emigrate to the Americas in 1634, but was prevented from doing so.

After moving to farm in Cornwall, for several years, Cromwell and his family returned to Ely in the late 1630s as an established member of the gentry, committed Puritan and well-connected politician.

Listen Now

Listen Now4. When civil war broke out, he had little military experience

When war rolled around in 1642, Cromwell had only ever participated in local militia. However, he quickly gathered troops and blocked a shipment of silver plate from Cambridge colleges to the king, and tried to participate in the Battle of Edgehill, but arrived too late to be of any use.

Fortunately there were plenty of other opportunities for Cromwell to develop his tactical skills, and he impressed his superiors at the Battle of Gainsborough, amongst several other skirmishes in East Anglia.

5. He became key to the Parliamentarians’ success

Cromwell subsequently oversaw notable victories at Marston Moor and Naseby, and was the only MP who was excluded from the Self-Denying ordinance, allowing him to retain his role in Parliament and his military command.

He also helped spearhead the founding of the New Model Army, which was based on skill and ability rather than social status: a new innovation at the time. Close cavalry formations, another innovation, and strict discipline also helped bring success.

Statue of Oliver Cromwell in Parliament Square

Image Credit: Prioryman / CC

6. Cromwell was one of the more enthusiastic regicides

The question of what to do with the deposed Charles I plagued the Parliamentarians. Many of them felt that killing the king was wrong: the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings rang deep. Others argued that the war would never be over while Charles remained alive.

Cromwell was the third to sign Charles’ death warrant, and co-signed the actual warrant to proceed with the beheading, which took place on 30 January 1649.

Listen Now

Listen Now7. Cromwell’s Irish campaign remains controversial

Ireland remained predominantly Catholic and had made an alliance with the Royalists which had the potential to pose a serious threat to the newly founded Commonwealth of England. As a result, Parliamentarian forces invaded Ireland in 1649, sacking and capturing a number of strategically important towns and ports in brutal, bloody and protracted sieges.

The conquest of Ireland took 3 years to complete, and Cromwell’s legacy in Ireland remains one tainted by bloodshed and bitterness. Civilians, as well as those bearing arms, were subject to violence and some historians have dubbed his actions in Ireland as being reminiscent of ethnic cleansing in their brutality.

8. Lord Protector – for life

In December 1653, Cromwell was made ‘Lord Protector’ for life: a role not entirely dissimilar to that of a monarch. He was called ‘Your Highness’ and had the power to call and dissolve parliament. In 1657, he was ceremonially re-installed as Lord Protector at Westminster Hall in an event which closely mirrored a coronation.

The main aim at this point was ‘healing and settling’ the nation following nearly a decade of civil war, as well as implementing social and moral reforms to firmly establish ‘godliness’ at the heart of England. The office of Lord Protector was not hereditary, but Cromwell could nominate his own successor.

9. Cromwell’s rule was ambitious

Not content to simply heal the nation, Cromwell launched an ambitious foreign policy, including the ‘Western Design’ (which was effectively an armada against the Spanish West Indies) and a treaty with the avowedly Catholic France to supply troops and weapons in their war against Spain. Jews were allowed to re-enter and settle in England following their expulsion in 1290 in the hope that they would aid economic and commercial recovery in England.

The Protectorate, as the period between 1653 and 1658 was known, relied heavily on Cromwell’s ability to keep control of both Parliament and the army. A popular military leader and an experienced politician, he managed to balance these two powerful forces in a way which no one else could.

10. He was posthumously executed

Cromwell died in September 1658, possibly from septicaemia following a urinary infection. He was buried with great pomp and circumstance at Westminster Abbey with a funeral based on that of James I.

Two years later, in 1661, his body was exhumed and subject to posthumous execution. His head was then displayed on a spike outside Westminster Abbey until 1685. It changed hands several times subsequently before being reburied in 1960 at Sidney Sussex College Chapel, Cambridge.

Watch Now

Watch Now