While it is true that Britain was not the very first nation to abolish its slave trade (the Dutch did so in 1792), it was the first nation with an Empire to abolish the institution of slavery in all of its dominions in 1833.

The following 10 people were instrumental figures in the campaigns to see both the slave trade and the institution of slavery abolished across Britain’s Empire.

1. Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp. Image Credit: Public Domain

Born the son of a clergyman in 1735, Granville Sharp’s interest in slavery with the Empire began in 1765 after he befriended a slave called Jonathan Strong in London, who had been badly beaten by his owner.

Using his expertise in civil service, Sharp took a successful case to the lord mayor in London and Strong was freed. This would not be the last time Sharp devoted his attention to helping enslaved persons through legal means.

In 1772 he became heavily involved in securing the court ruling by Lord Mansfield, during a case in which he acted as a lawyer for the runaway slave James Somerset, concluding that a slave would become free the moment they set foot on English territory.

Again in 1783, Sharp became involved in a legal battle to see those involved in the Zong Massacre brought to justice. He met up with the other prominent abolitionist Olaudah Equiano who had brought to his attention the horrors that had occurred onboard the slave vessel.

“The Slave Ship” by J.M.W. Turner, 1840. Turner depicts the events of the Zong Massacre in 1781. Image Credit: Public Domain

Whilst the criminal charges Sharp brought against the perpetrators were not upheld, the court ruled that the Zong’s owners could not claim insurance on the slaves. Cases such as this help to raise public awareness of the horrors of slavery and started to turn public opinion against the slave trade.

Sharp’s biggest contribution to the anti-slavery cause came in May 1787, when he joined with Thomas Clarkson and nine Quakers, to form the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. While he witnessed the achievement of this goal, he was not to see the final abolition of slavery in the British Colonies, as he died on 6 July 1813.

2. James Ramsay

James Ramsey was a Scottish naval surgeon, who had been stationed in the West Indian colonies and had lived on the island of St Kitts from 1762 to 1777.

The curate commented on the inhumane treatment he had personally witnessed whilst living in the Caribbean in his Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves published in 1784.

James Ramsay. Image Credit: Public Domain

As an evangelical pastor, Ramsey was keen to stress that those involved in the brutal traffic, who would be willing to sacrifice their profits in order to ameliorate the conditions of slaves would be rewarded by God. He also mentioned the benefits of ending the trade in terms of its promotion of Christianity amongst slaves, hopeful many of them would convert to the faith.

These were the first anti-slavery works by a mainstream Anglican writer who had personally seen the suffering, and were, therefore, very influential. Ramsay met with William Wilberforce in 1783 and Thomas Clarkson in 1786, of whom he encouraged in his efforts to obtain first-hand evidence of the trade.

Watch Now

Watch NowWhen Ramsay published An Address to the Public, on the Proposed Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1788, new attacks were made on his character in the House of Commons. Ramsay, deeply upset, became ill and did not live to see the abolition of the slave trade, dying in 1789.

3. Thomas Clarkson

Like Sharp, Thomas Clarkson was also born the son of a clergyman in 1760. He became a central figure in the campaign against the slave trade from the moment he wrote his award-winning essay, On the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, in 1785 (later published in 1786) whilst he was a student at the University of Cambridge.

He, Sharp and 9 other Quakers members formed the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787, a group committed to ending the traffic of enslaved Africans on British ships.

Thomas Clarkson. Image Credit: Public Domain

Aside from this, Clarkson’s biggest contribution to the anti-slavery cause was his accumulation of physical evidence in the form of slave chains, leg-shackles, thumbscrews, branding irons and whips – all items that could be used when lobbying for abolition in Parliament.

Clarkson rode 35,000 miles across Britain to visit some of its principal slave port cities such as Bristol, Liverpool and London in order to amass vast quantities of numerical data that confirmed the brutality of the ‘Middle Passage’, the stage in which millions of Africans were transported in slave ships across the Atlantic to the Americas.

Using the information he had received from interviews with over 20,000 sailors, Clarkson was also able to accurately calculate the mortality rate aboard slave vessels by the time they had reached the other side of the Atlantic. All of the evidence he had amassed was used by William Wilberforce in his speech to the House of Commons in 1789 and helped prove beyond any reasonable doubt the immorality of the traffic to those in Parliament.

Listen Now

Listen NowAfter the trade was abolished in 1807, Clarkson did not stop his work for the anti-slavery cause supporting the Anti-Slavery Society (formed in 1823) by travelling 10,000 miles across the country to build support for its goal, which was eventually achieved in 1833. Beyond this, Clarkson met abolitionists from the United States such as Fredrick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison.

He continued to write letters and pamphlets and address public meetings locally, until his death at Playford Hall in 1846.

4. William Wilberforce

By far the most well-known abolitionist, William Wilberforce became the figurehead of the abolition cause in Parliament. His position as the MP for Kingston upon Hull and subsequently Yorkshire in the late-18th and early-19th century meant that he was vital to the anti-slavery campaign in terms of lobbying for support of an abolition bill in the House of Commons.

William Wilberforce. Image Credit: Public Domain

A deeply religious man, Wilberforce had always been interested in social reform since his youthful days as a politician and student. He was initially concerned with improving factory conditions for poor workers in Britain. It was not until Thomas Clarkson brought physical and written evidence demonstrating the brutality of the slave trade to his attention, that Wilberforce became committed to the anti-slavery cause.

The trafficking of Africans across the Atlantic and the institution of slavery itself were both morally reprehensible and so he fought tirelessly throughout the last decade of the 18th century to bring forward motions for abolition bills in Parliament. He was the voice of the cause where it truly mattered – in government.

Despite multiple setbacks, Wilberforce’s bill to terminate Britain’s slave trade eventually passed in the House of Commons and was given royal assent on 25 March 1807.

Slave Trade Act of 1807. Image Credit: Public Domain

Once the slave trade had been abolished, Wilberforce set his sights on abolishing the institution of slavery itself in British dominions. He became a founding (yet admittedly inactive) member of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823 and wrote his famous Appeal in the same year, a treatise urging that total emancipation was morally and ethically required.

Although emancipation was resisted in government for ten years, Wilberforce’s efforts were not in vain. A month after his death in London on the 29 July 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 was passed.

5. Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano. Image Credit: Public Domain

Olaudah Equiano has been revered in history as one of the most influential abolitionist figures. Born sometime around 1745, Equiano had been kidnapped from his tribe in the former Kingdom of Benin (Nigeria) and sold into slavery at the young age of 11.

For the next ten years of his life, Equiano went on quite the journey. Having experienced the infamous Middle Passage and the horrors that entailed, Equiano was fortunate enough to befriend his owner, a Royal Naval Officer named Michael Henry Pascal.

Pascal took a liking to Equiano, whom he renamed Gustavus Vassa, and had him sent to England to be educated. This education allowed Equiano to become an independent trader and eventually save up enough income to buy his own freedom.

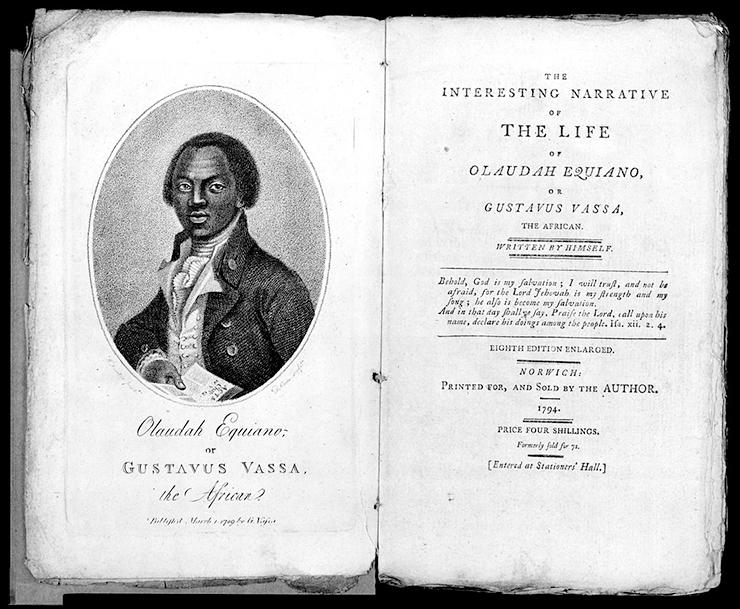

Equiano documented all of these experiences in his autobiography entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, published in 1789. The book became a best-seller and nine editions were published in his lifetime.

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African. Image Credit: Public Domain

The former slave had been involved in the abolition movement since the early 1780s, assisting Granville Sharp in his legal proceedings and having joined the ‘Sons of Africa’ group, yet it was his book that served as his biggest contribution to the campaign.

Not only had it riled up public support, but the testimony inside became extremely useful when it came to lobbying for abolition in Parliament.

Watch Now

Watch Now6. Ignatius Sancho

Born in 1729 on a slave-ship bound for Grenada, Ignatius Sancho was an African composer, actor and writer who would later become a devoted supporter of the abolitionist cause in Britain.

At the age of two, Sancho was brought to England by his owner, where he remained a slave for 18 years. Eventually Sancho ran way to the Montagu House, whose owner John Montagu taught him how to read and encouraged Sancho’s budding interest in literature.

Sancho taught himself to read and spoke out against the slave trade. He went on to compose music and write poetry and plays. He became very well-known and his shop in Westminster, that he had established in 1773, became a meeting place for some of the most famous writers, artists, actors and politicians of the day.

Ignatius Sancho. Image Credit: Public Domain

As a financially independent householder, he became the first black person of African origin to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain.

After his death in 1780, Sancho’s letters were published in a book, which became an immediate best seller. Five editions of the book were published and his writing was used as evidence to support the movement to end slavery.

7. Josiah Wedgewood

Famed as the ‘Father of English Potters’, Josiah Wedgwood (b. 1730) led English pottery from a cottage craft to a prestigious art form sustaining an international business. He was also an abolitionist and an extremely important figure within the campaign to end the transatlantic slave trade.

His interest in the anti-slavery cause derived from a friendship with the campaigner Thomas Clarkson. Using his expertise in the large-scale production of pottery, Wedgewood mass-produced a slave medallion supporting the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787.

Josiah Wedgwood’s medallion read ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ Image Credit: Daderot / CC.

The logo on the medallion itself depicted a knelt and shackled slave seen to be uttering the words “Am I not a man and a brother?”.

This emblem was worn on bracelets, medallions and was stamped onto pottery and kitchenware. It was even seen on contemporary tobacco pipes. Here, branding enabled the public to express disapproval of the slave traffic and feel as though they were engaging in the debate. Many viewed the logo as an individual representation of their enlightened view of the world.

Josiah Wedgewood’s designed logo would became the one of the most famous images associated with the abolition campaigns – it allowed the Abolition Society to rile up public support that could not be ignored in Parliament.

8. William Grenville

Not only was Lord William Grenville the Prime Minister in 1807 when Britain abolished the slave trade, but he himself played an active and prominent part in ensuring the bill was passed in Parliament.

William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville. image Credit: Public Domain

Born in 1759, William Grenville was born into a family of elites. His father was a Whig politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom between 1763 and 1765. This allowed William, even at a young age, to mix with some of the country’s leading men – those who were capable of enforcing change.

Grenville had always detested slavery, considering it not only to be immoral but impractical. Influenced by the revolutionary economist Adam Smith, the future Prime Minister thought slavery as one of the most inefficient forms of labour and also the most dangerous for the proprietor.

Having become a close ally to his cousin William Pitt the Younger, who served as the Prime Minister for two terms and was also a keen critic of the slave trade, Grenville quickly established himself as one of the leading British ‘Pittite’ Tory politicians.

Although his cousin Pitt had always claimed that he had wanted to see the abolition of the slave trade, he never committed to advising those in Parliament how to vote on it – he always viewed it as a question of conscience. And so, those in his party were given free reign to vote against any bill. Grenville would not make the same mistake.

After Pitt’s death in 1806, William Grenville asked to form a coalition government of national unity. As soon as he was power, Grenville dedicated his time to see an abolition bill passed in Parliament. He himself introduced the bill to the House of Lords, which had proven to be a huge stumbling block to passing abolition in the past.

Listen Now

Listen NowGrenville made a powerful speech, moving for the second reading of the bill on 5 February 1807. He denounced economic objections by declaring that the West Indies planters already produced more than they could sell and continuation would result in their ruin.

Grenville’s strongest asset, that proved to be invaluable to the abolition campaign, was his ability to recognise that in order to successfully pass a bill in parliament, he had to promote it on the grounds that it supported national as well as colonial interest.

9. John Newton

An unlikely abolitionist, John Newton was a former slave ship master from London, born in 1725. At a young age, Newton worked on slave ships and became increasingly involved in the slave trade.

Astoundingly, Newton was enslaved himself in 1745 when crew members of the slave ship Pegasus left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye of the Sherbro People. She abused and mistreated Newton just as much as she did her other slaves.

Early in 1748 Newton was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton’s father to search for him, and he returned to England. Perhaps as a result of the humbling and horrific experience, Newton had a spiritual conversion on the return voyage, which almost resulted in the ship sinking.

John Newton in 1807. Image Credit: Public Domain

After giving up seafaring and having devoted himself to Christianity, Newton became well known for his pastoral care and respected by both Anglicans and nonconformists. After his conversion, Newton began to deeply regret his involvement in the Slave Trade.

His advice was sought by many influential figures in Georgian society, among them a young William Wilberforce. Newton was able to encourage Wilberforce to stay in politics and fight to abolish slavery.

In 1787, Newton wrote a tract supporting the abolition campaign, Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade, which was very influential. It graphically described the horrors of the Slave Trade and his role in it.

Despite all his contributions to the abolition campaign, Newton is best-known for his collaboration with William Cowper to produce a volume of hymns, including ‘Amazing Grace‘.

10. James Stephen

Born in Poole in 1758, James Stephen spent much of his youth in a debtors’ prison. Growing up, many described him as a volatile and bad-tempered child, traits which he didn’t seem to rid himself of as an adult. Although he was a prolific newspaper reporter and lawyer, Stephen foolishly involved himself with his best friend’s fiancé, resulting in him sailing to Barbados to avoid any scandal.

Whilst in the Caribbean and having become the solicitor-general of St Kitts, Stephen witnessed several trials that resulted in grave miscarriages of justice against slaves. After seeing such occurrences, Stephen vowed to never own slaves himself and to join the abolitionist cause.

James Stephen. Image Credit: Public Domain

He began to correspond with Wilberforce, sending information back about the inhumane treatment of the enslaved. When he returned to England, he became part of a group of evangelical Christians working with Wilberforce and married his sister, Sarah, in 1800.

Like William Grenville, Stephen was a pragmatist. He knew that an abolition bill would not pass in Parliament purely on moral grounds and so used his sharp legal mind to argue from a practical standpoint.

His greatest contribution to the abolitionist cause was his ability to disguise the Foreign Slave Trade Act of 1806, legislation that banned the trafficking of Africans to foreign colonies, as a patriotic war-time measure aimed at hindering Napoleon’s war effort. Having reinstated slavery in the French colonies, Napoleon’s decision allowed abolitionists such as Stephen to pair abolitionism with patriotism.

Watch Now

Watch NowThe Foreign Slave Trade Act of 1806, which came in part as a reaction to Stephen’s book War in Disguise, Or the Frauds of the Neutral Flags published a year earlier, was the first piece of substantial legislative reform that had been achieved by the campaign in over a decade and effectively had cut of two-thirds of the British slave trade. It paved the way for the Abolition Act of 1807.